The Bank of Thailand theory of everything (English version)

Why the Bank of Thailand's policies are at the heart of many of the problems in the Thai economy.

Thailand’s economy has grown slowly over the past 10 years, averaging only 1.9% per year. Most economists attribute the slow growth to structural problems. They have proposed reforms that are deemed necessary for jumpstarting growth. The problems in the Thai economy are as follows:

High household debt

Lack of competitiveness of SMEs

Lack of export competitiveness

Low private investment growth

Slow productivity growth

Economic growth that has been clustered in major cities

Inability to attract FDI

Poverty & inequality

The housing theory of everything proposes that all of the major problems in the Western world are caused by a shortage of housing.

I propose that the ‘Bank of Thailand theory of everything’ explains many of the economic problems that Thailand is facing.

Monetary policy

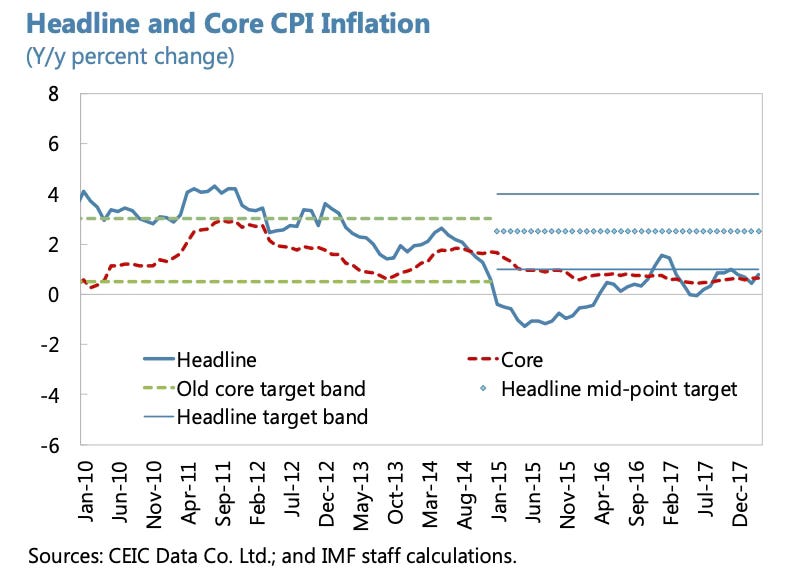

The Bank of Thailand is an inflation-targeting central bank. Inflation targeting began in 2000 with a core inflation target.

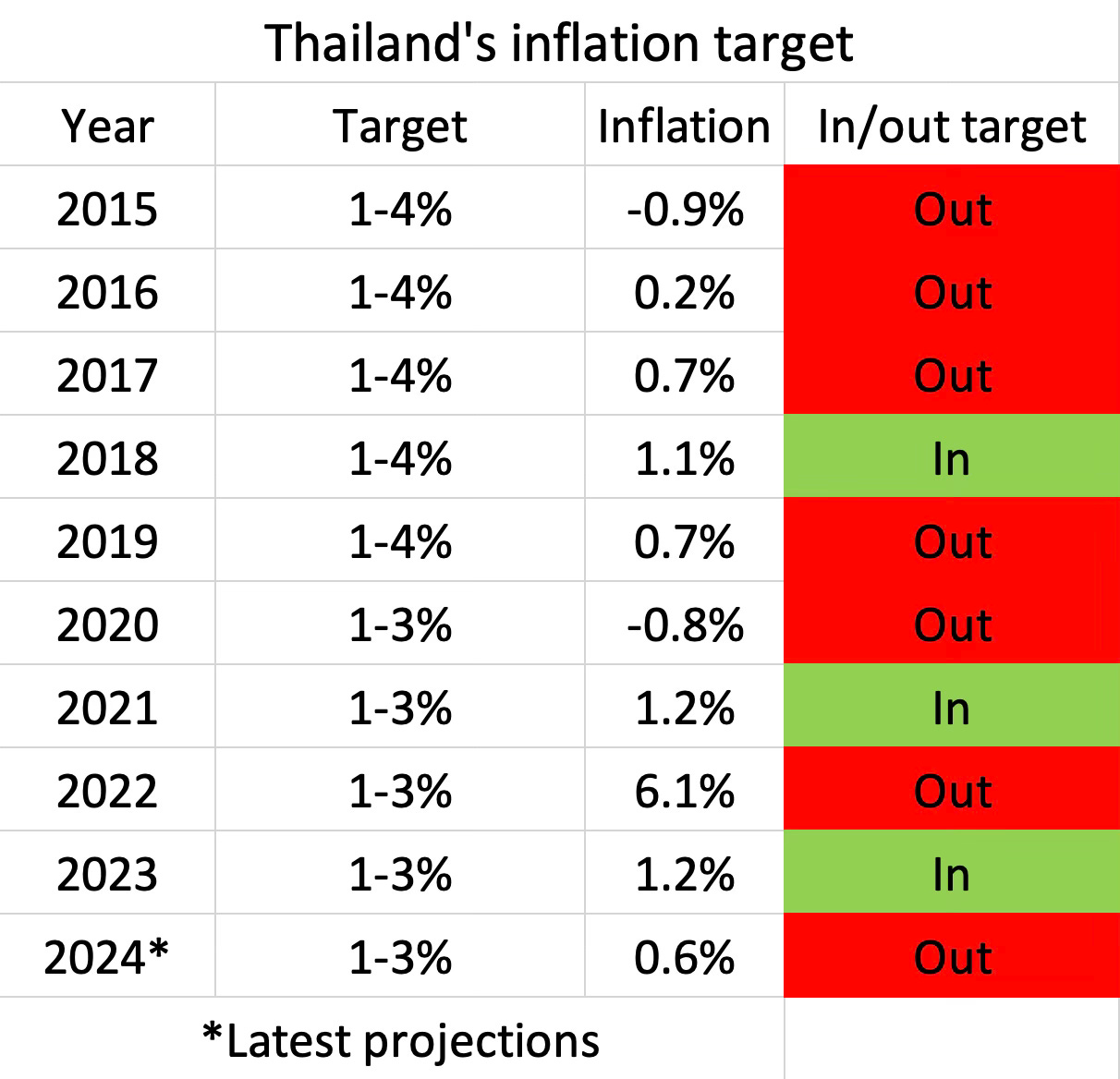

The target was changed to a headline inflation target range in 2015 of 1-4% up to 2019, after which it was changed to 1-3%. How do we judge if monetary policy has been too tight or too accommodative? By looking at inflation.

Judging by how often the target has been missed and the direction of misses, monetary policy has been too tight. Over the last 10 years - including projections for 2024 - the inflation target has been missed in 7 years. Out of those 7 years, 6 were missed on the downside. In 2018, 2021, and 2023, inflation was barely within the lower bound of the target range.

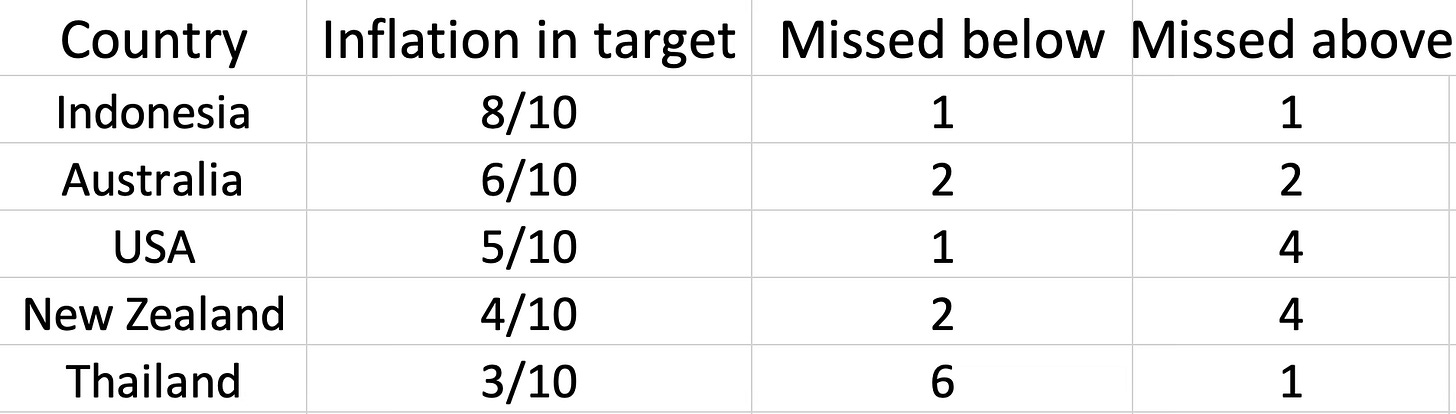

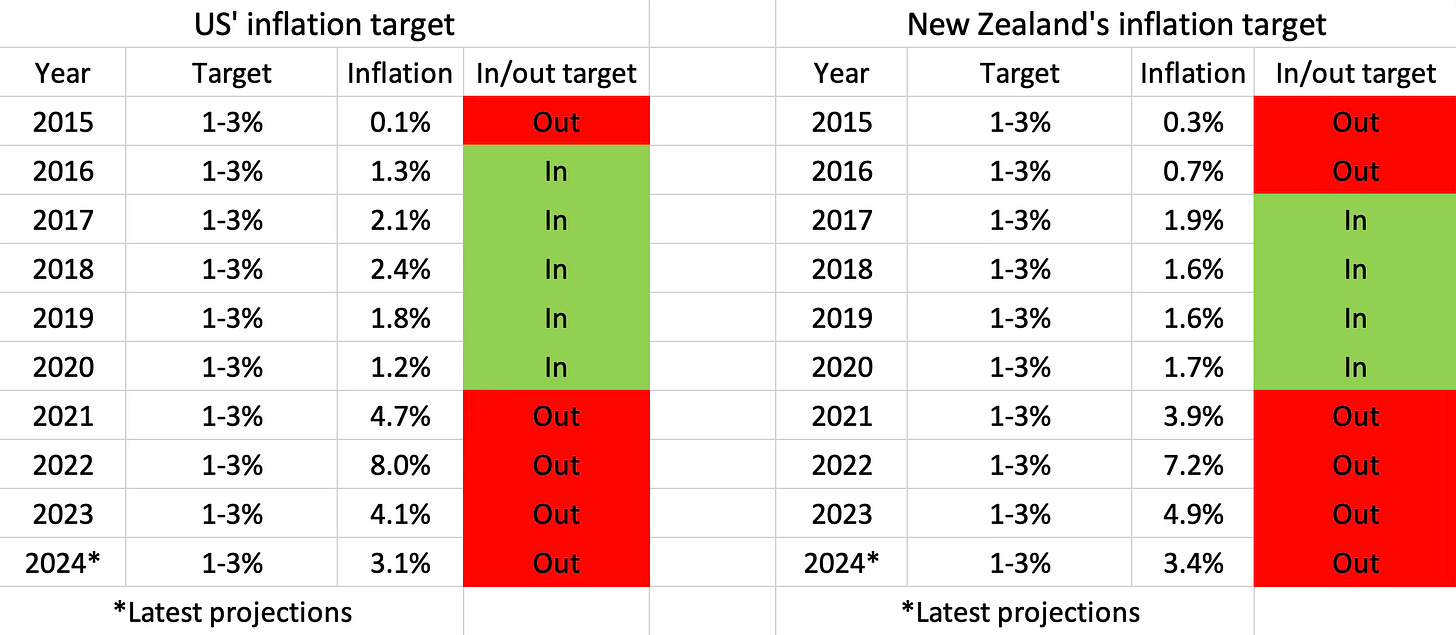

Tight policy can also be demonstrated by comparing performance with other central banks. To make comparison possible, I converted each country’s target into a range similar to Thailand’s. Comparing the Bank of Thailand’s performance with central banks in Indonesia, Australia, the US and New Zealand over the last 10 years, the Bank missed its target more often and also undershot it more frequently. Projections for 2024 are from April.

Indonesia and Australia hit their targets more often, and when the target is missed, it’s missed both above and below, suggesting no bias in policy-making.

New Zealand and the Fed missed their targets less often than the Bank of Thailand, but miss them above their targets more often, suggesting a bias towards overstimulating.

The directional bias in the Bank’s monetary policy is clear.

As the Federal Reserve says:

The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy

Overall headline inflation has averaged only 1% over the last 10 years. Economists at the Bank explained the low inflation prior to 2020 by citing global factors. Low oil prices were also a factor cited, given that Thailand is an energy importer and energy is a relatively big share of the CPI basket. However, inflation was especially low in Thailand relative to regional countries and lower than in developed markets like the US and the EU.

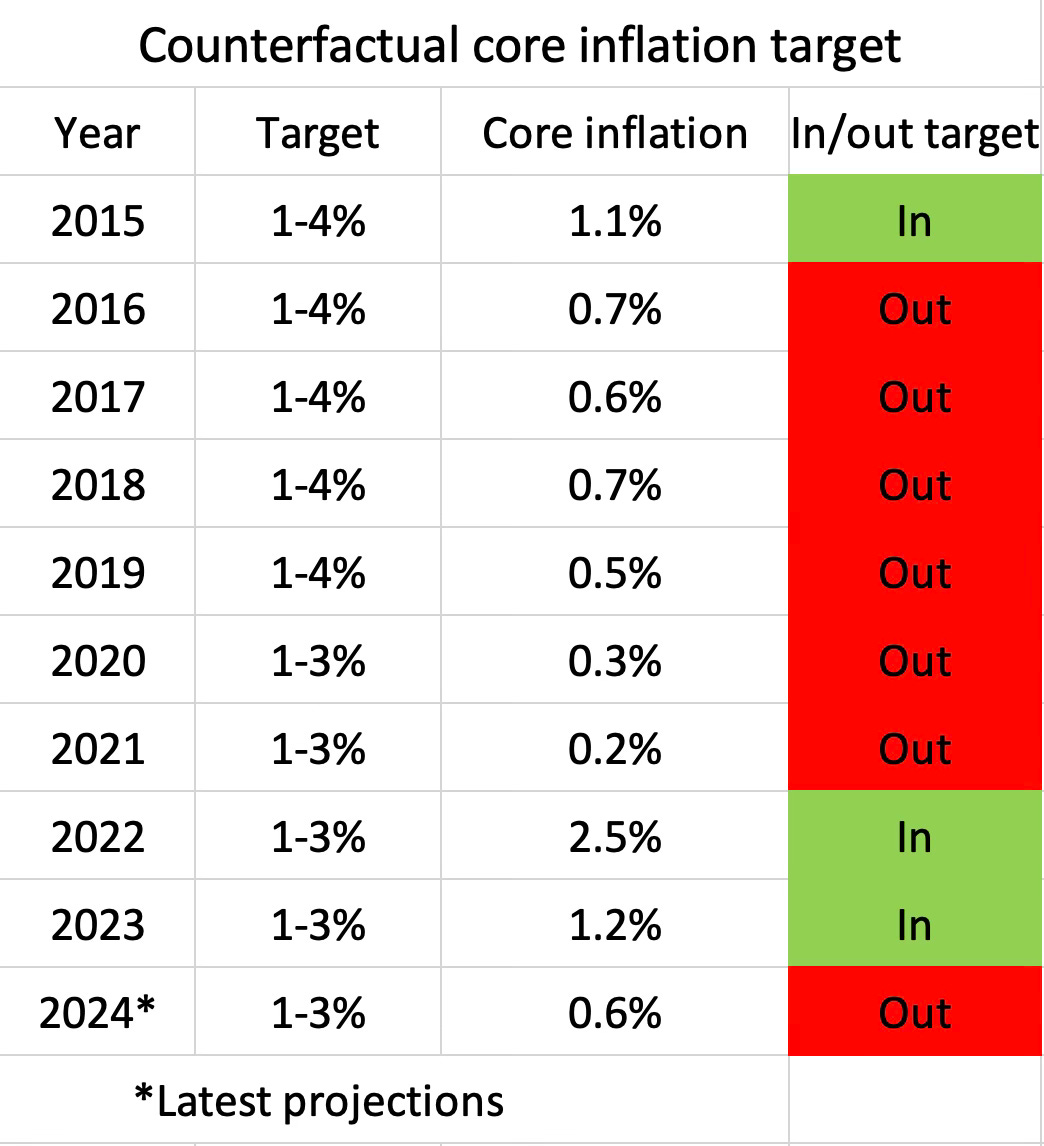

Taking a look at core inflation, we can see the same trend. Core inflation has averaged only 0.9% over the last 10 years. In a counterfactual world in which core inflation was the target instead of headline inflation, the Bank would have still missed its target in 7 of the last 10 years. In 2015 and 2023, core inflation was barely within this counterfactual target.

Low global energy prices and low global inflation do not explain the Bank’s persistent undershooting of the target. Tight monetary policy does.

The post-covid global increase in inflation also makes the explanation for low inflation prior to that less believable. Central banks learnt from their response to the Great Recession, and during covid they stimulated much more forcefully and used more tools. Many countries have stubbornly high inflation today. The Bank didn’t learn the same lessons, and post-covid was too quick to withdraw stimulus. Thailand today has the same problem it did before covid: inflation that is too low and persistently undershoots the target.

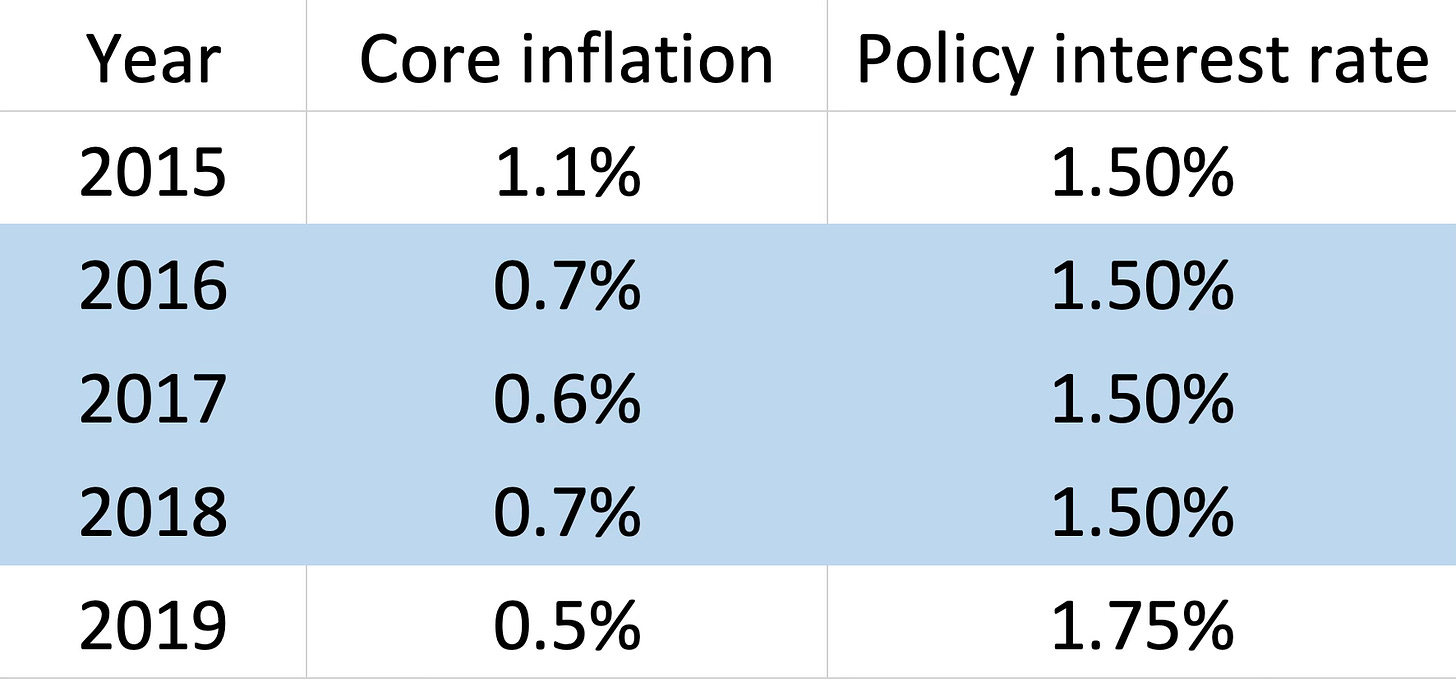

After inflation rose to nearly 8% in 2022, the Bank raised rates enough to bring it down to 3% by March 2023, which was within the target range. However, rates were raised a further 3 times to 2.5%.

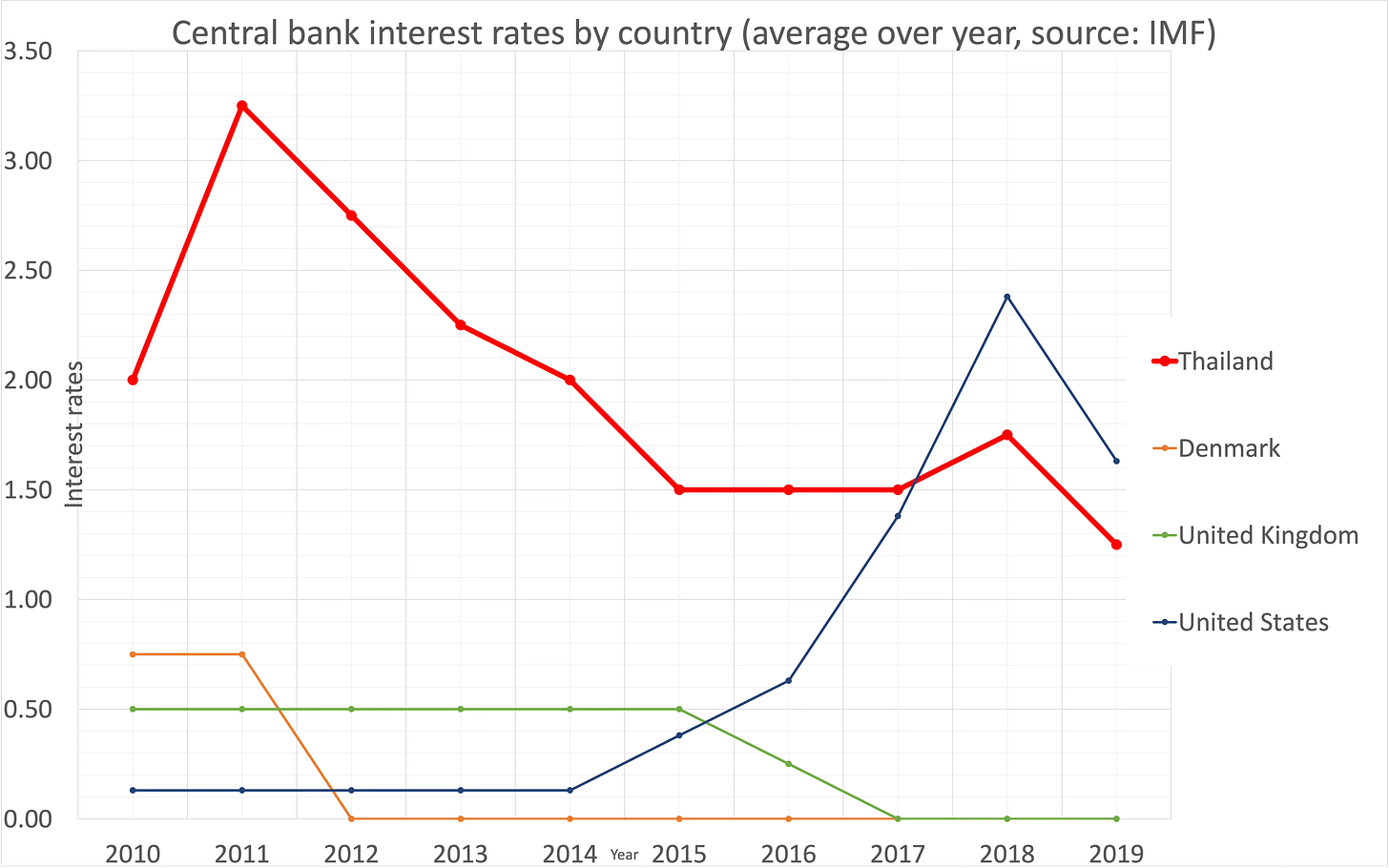

One explanation for the rate increases was that interest rates in Thailand were still low and policy space was needed to be built for the future. Economists at the Bank said that rates were then very low compared to global rates. But determining whether interest rates are high or low requires a reference to inflation. If inflation is low, interest rates will be low. If inflation is high, interest rates will be high. Interest rates in Thailand have been among the lowest in the world because inflation has been among the lowest in the world.

The Fed cut rates in 2019 to 1.75% and raised rates in 2022 to 5.5% in response to inflation data and outlook; they did not say rates were too low or too high without referencing inflation.

But unbelievably, that was one of the justifications for the rate increases after inflation came down below the upper end of the target range in Thailand. Even today, Governor Sethaput routinely says that Thailand has one of the lowest interest rates globally without referencing inflation. Vice Governor Piti says the same in briefings.

Tight monetary policy also forced the Finance Ministry to compensate with fiscal deficits. At times, the Bank argued in favor of fiscal policy even while monetary policy was an option. In September 2020, in the middle of the biggest recession in Thailand for nearly 30 years, the Bank explained its decision to hold rates as follows:

The Bank of Thailand held its benchmark interest rate unchanged for a third straight meeting to save its limited policy space, allowing fiscal policy to take the lead in reviving an economy headed for its worst annual performance ever.

An Assistant Governor said:

In a briefing after the decision, Assistant Governor Titanun Mallikamas said central bank policy remained accommodative but fiscal policy should be the driving force in a recovery, focusing on jobs and economic restructuring.

“Going forward, government policies from various agencies needed to be more targeted and timely,” he said.

The Bank has erred towards tighter policy. Research suggests that tight monetary policy can reduce potential output even after a decade. Employ America sums the study up here:

A 1 percentage point shock to the short-term interest rate results in a GDP decline of 4.6% twelve years after the shock. Both capital and productivity decline, but the bulk of the decline in GDP is explained by the decline in productivity.

Tight monetary policy led to many of the problems that the Thai economy has today.

The Thai economy’s issues

Why interest rates are used

The Bank’s management has repeated the phrase ‘interest rates are a blunt tool’ for years. The Bank implies that interest rates are not meant to be used as a tool to solve sectoral problems, suggesting that most of the problems in the Thai economy are due to supply issues.

Central bankers like Jerome Powell are explicit about the purpose of the central bank’s tools:

the Fed's tools work principally on aggregate demand

Are the issues in the Thai economy due to a lack of demand or supply?

Slow growth

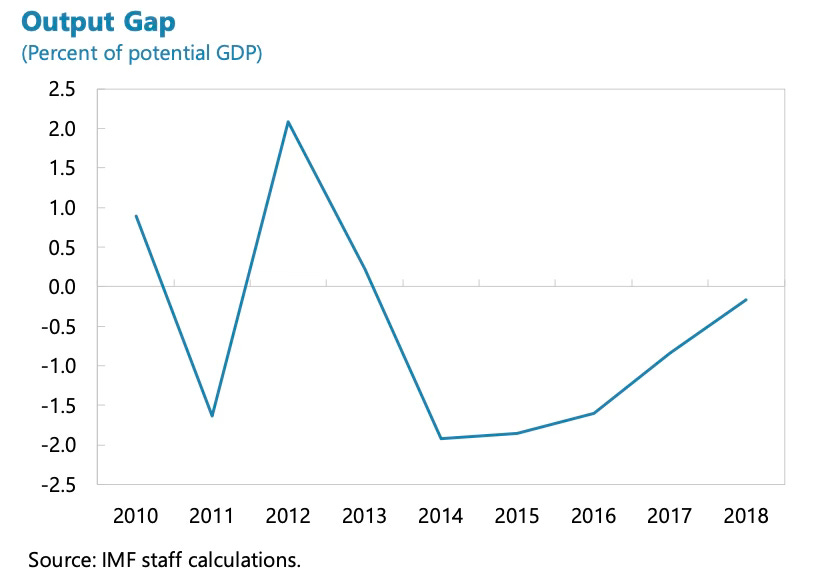

Tight monetary policy led to below target inflation. It also led to below-potential growth. In the 2019 Article IV report, the IMF modeled the output gap and suggested that it had been negative for many years. A negative output gap suggests an economy with weak demand.

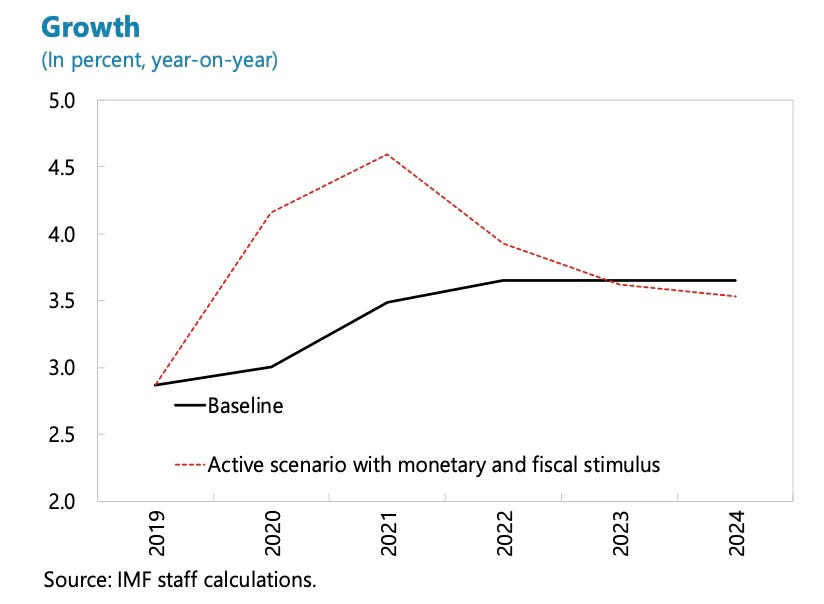

IMF prescriptions are usually conservative, but even it suggested easing monetary policy in 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2019 and modeled the effects on growth.

The Bank tightened policy in 2018, after which the economy experienced a drastic slowdown to the surprise of the Bank’s economists.

The Bank only eased at the end of 2019 after the economy suffered the largest quarter-on-quarter contraction since the Great Recession.

Nominal GDP grew only 3%/year over the last 10 years. Most businesses in Thailand have complained of the difficulty of increasing revenue. Even businesses in sectors that have grown such as hospitality have not experienced the growth rates common in neighboring countries.

What is the correct action to take if the economy is growing below potential? Jerome Powell explains it here in reference to the Fed’s response to the Great Recession:

economic activity remained far below its potential, and the need for highly accommodative policy seemed clear

Other central bankers such as Fabio Panetta of the European Central Bank say this about the output gap:

The output gap – the difference between actual and potential output – plays an important conceptual role in central banking.

In normal conditions, the output gap represents a gauge of inflationary pressure by signaling the amount of slack in the economy. In turn, this provides a yardstick against which central banks calibrate monetary policy. By steering demand so that actual output matches potential central banks can stabilise inflation around their targets.

High household debt

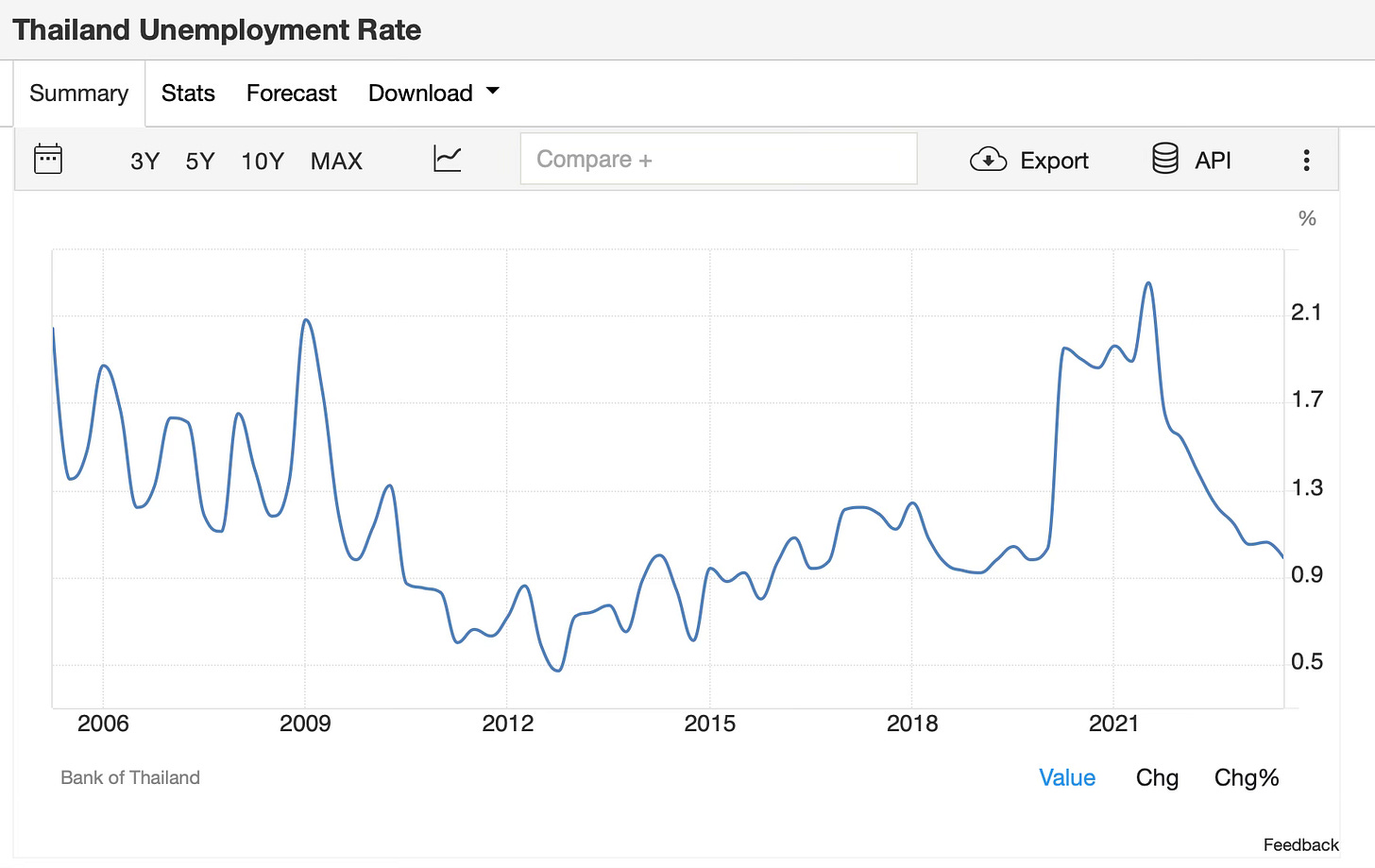

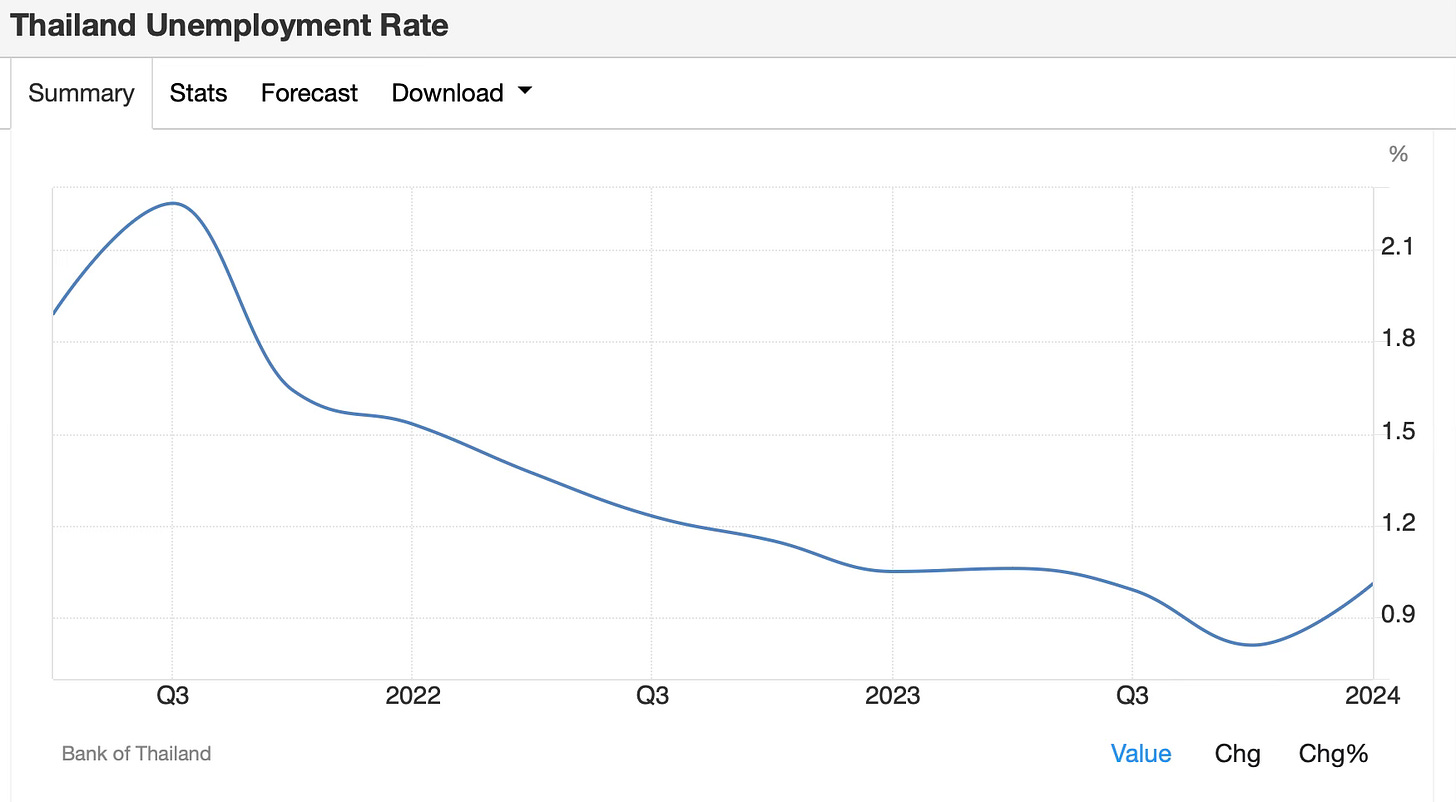

Similar to China, Thailand’s labour market is flexible as migrant workers who lose jobs can move back to the countryside to farm. The unemployment rate is thus not comparable to developed countries’.

Nonetheless, tight monetary policy had an effect that was noticeable on the unemployment rate. After the Great Recession, it bottomed in Q4-2012 at 0.5% then trended up as policy was tighter than conditions warranted.

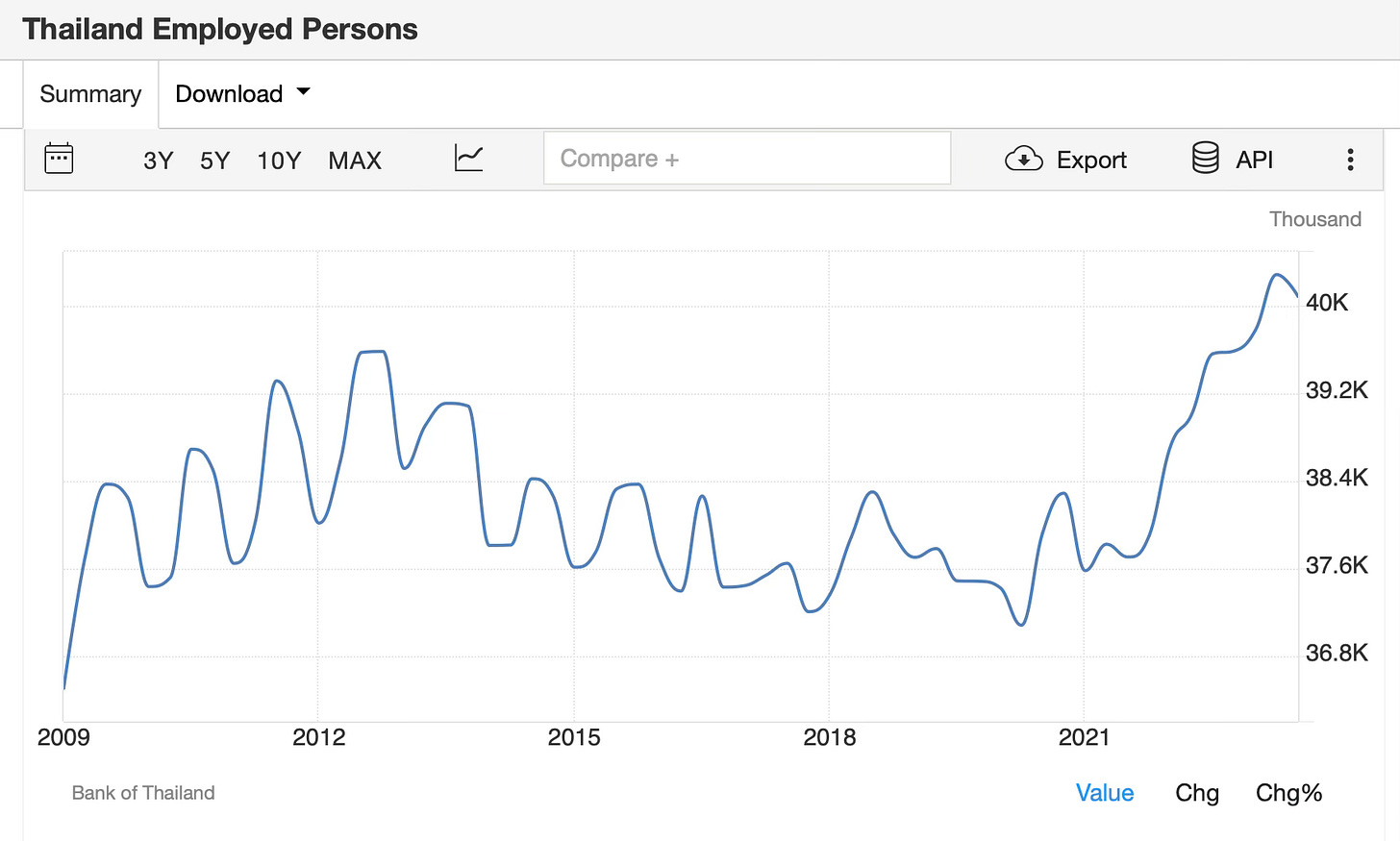

Other measures of labour market slackness confirms this. The total amount of people employed dropped in 2013 and trended down for years, suggesting a weak labour market.

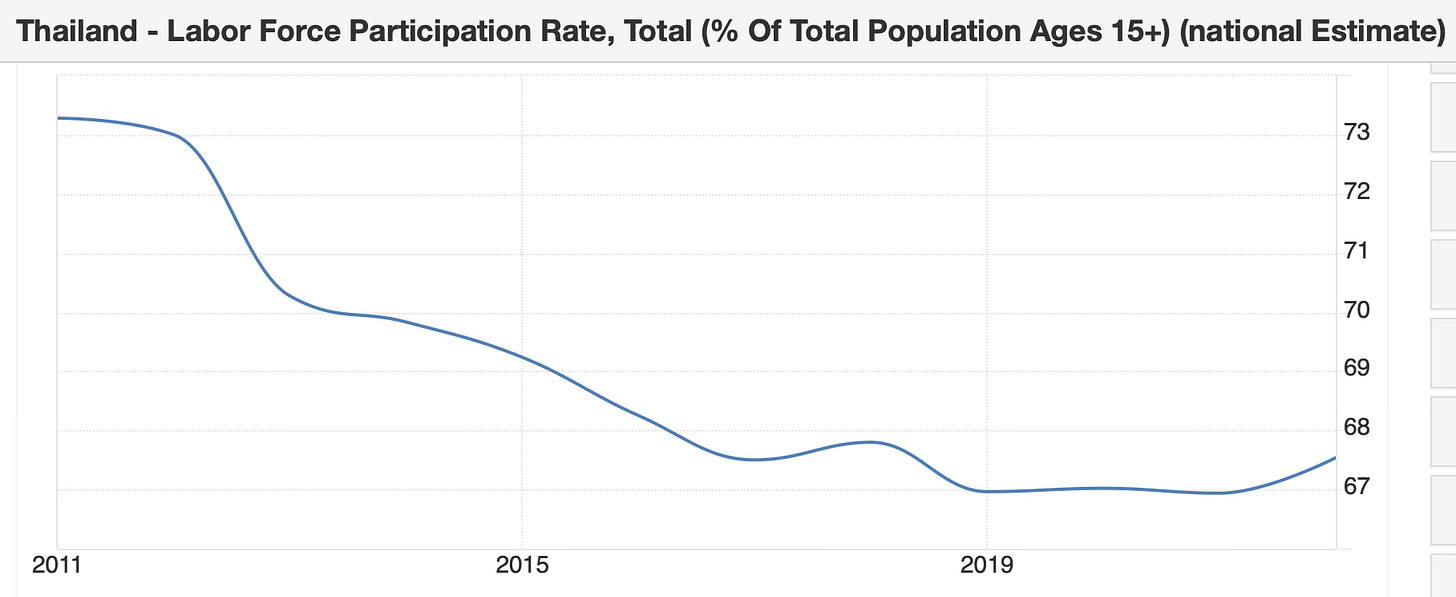

The labour force participation rate likewise trended down for years before picking up after the reopening after covid.

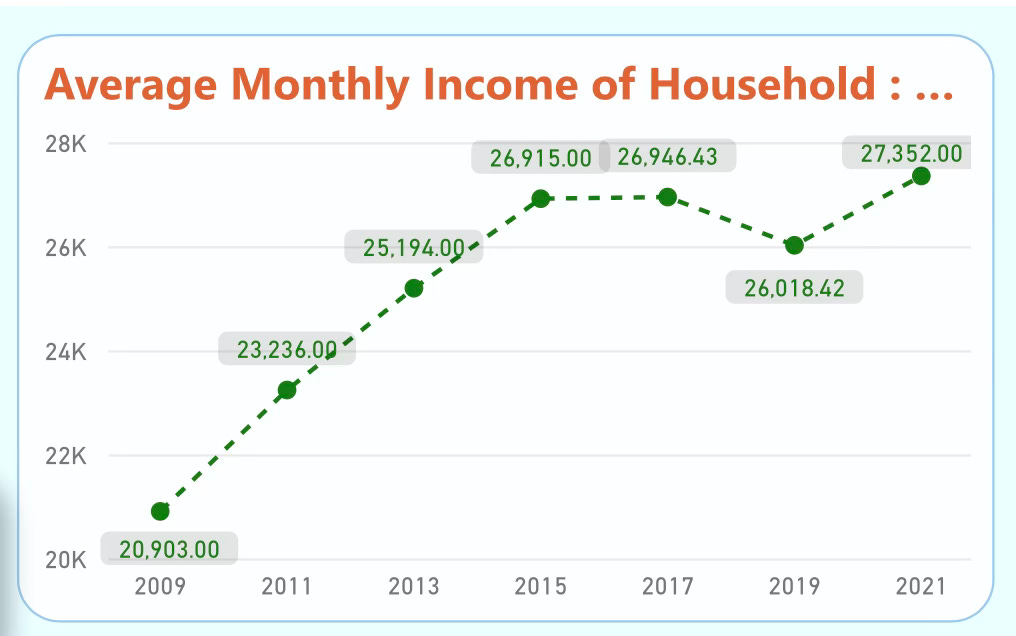

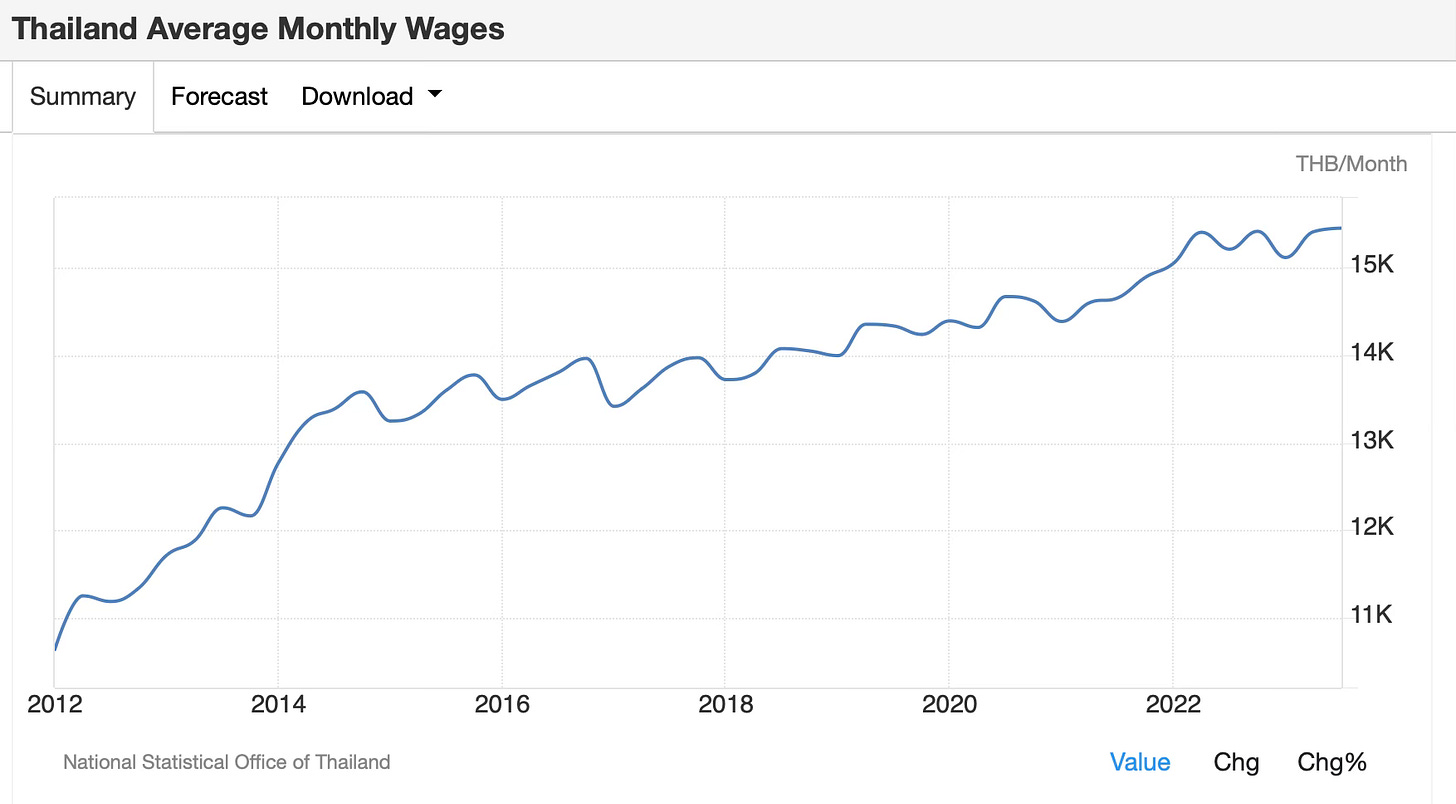

A slack labour market led to slow household income growth. Average nominal household income did not grow from 2015 to 2021.

Average wages grew slowly during this period.

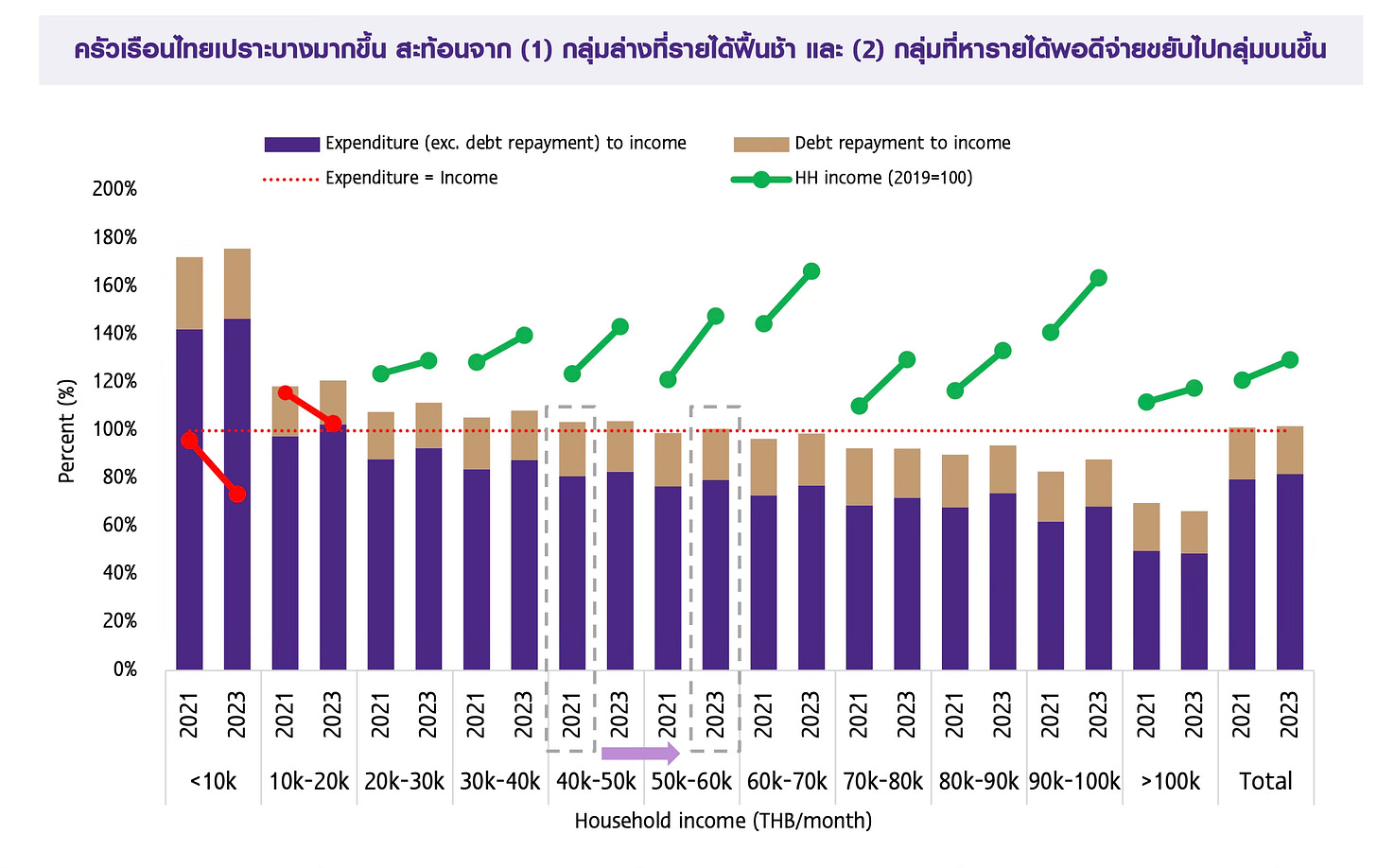

Low income growth led to worsening debt issues (reference: SCB EIC May 2024):

Approximately 50-60% of households earn less than 20,000 baht/month (~$550/month). For these households, incomes declined between 2021 and 2023. Predictably, their expenditure to income ratio increased, even without taking into consideration debt repayments.

Households accumulated debt as incomes did not keep pace with expenses. Tight monetary policy which led to a slack labour market lowered households’ ability to negotiate better wages and benefits. A slack labour market over the last 10 years suggests an economy dealing with a lack of demand, which most economists would say monetary policy has appropriate tools for resolving through boosting aggregate demand by cutting interest rates or depreciating the currency.

Lack of competitiveness of SMEs

Tight monetary policy led to an overvalued currency. Scarred by the Asian Financial Crisis, economic commenters in Thailand routinely reference the $/฿ rate. At the current level of $1/฿36.5, the baht is considered weak.

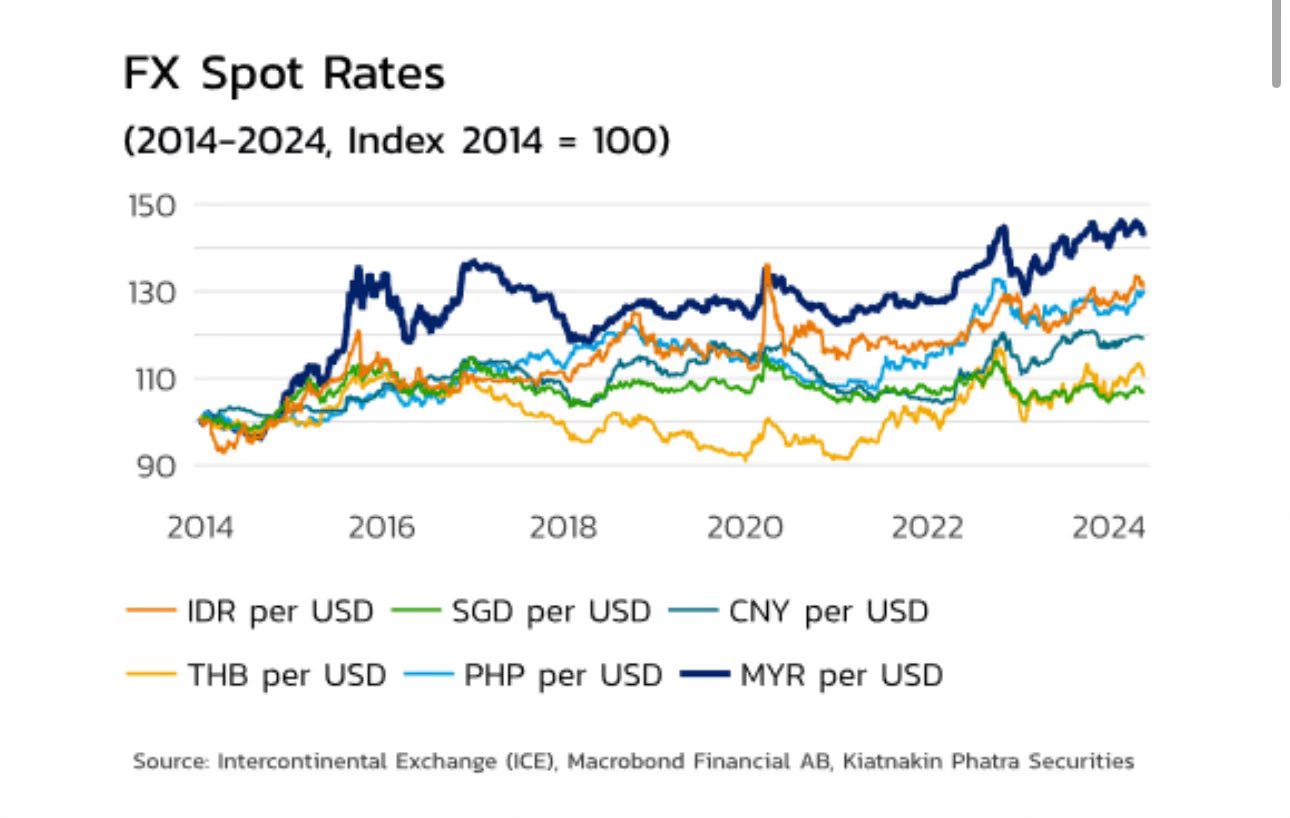

However, Thailand doesn’t compete in exports against the US. It competes against China, Vietnam, Indonesia and other neighbouring countries. Against these currencies, the baht has been stronger for almost all of the last 10 years.

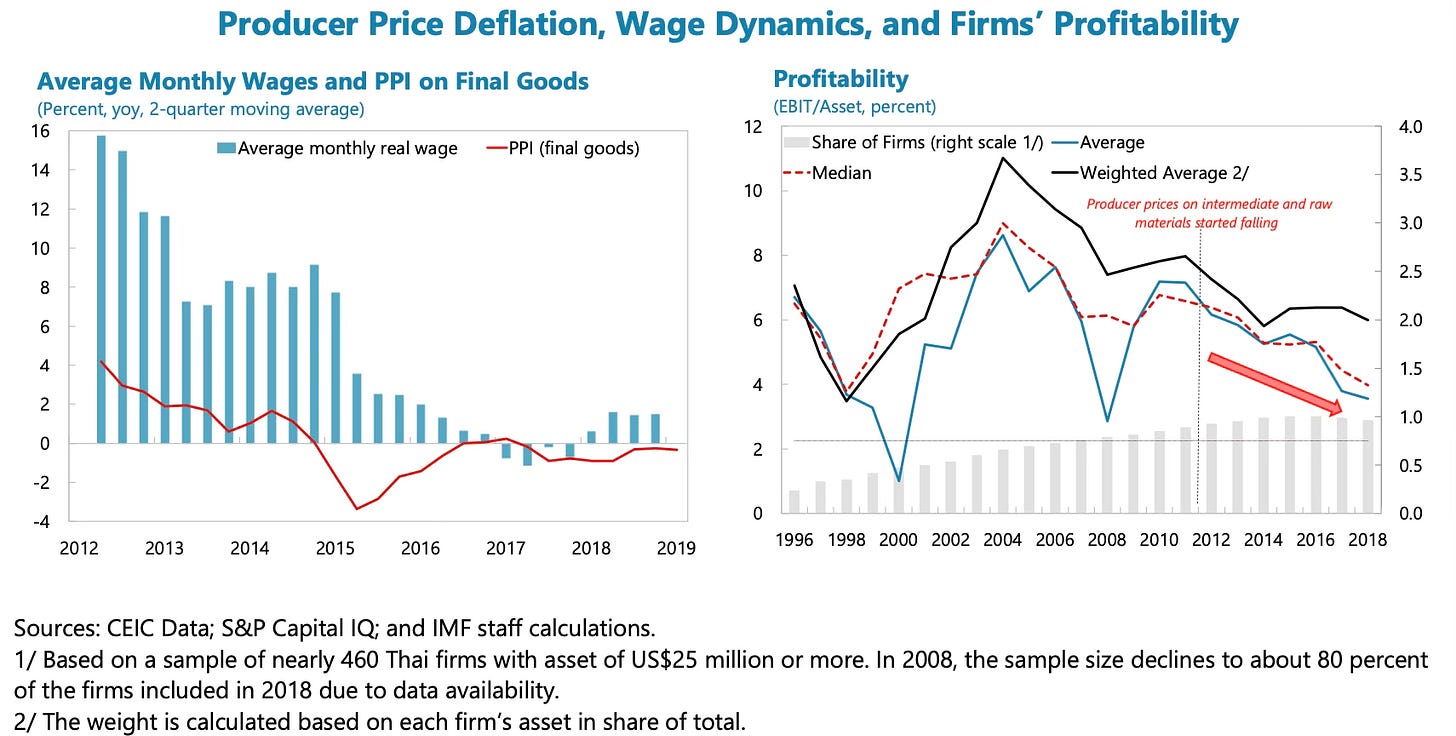

The overvalued baht has affected domestically-focused SMEs negatively, especially manufacturers. Traders that import consumer goods from China have benefitted instead. The overvalued baht makes it more profitable to import consumer goods from China than manufacturing it locally, and is one reason why the Thai-China bilateral deficit has ballooned. Chinese overcapacity exacerbated the issue, leading to slow or negative revenue growth as producer prices dropped during the period of tight monetary policy.

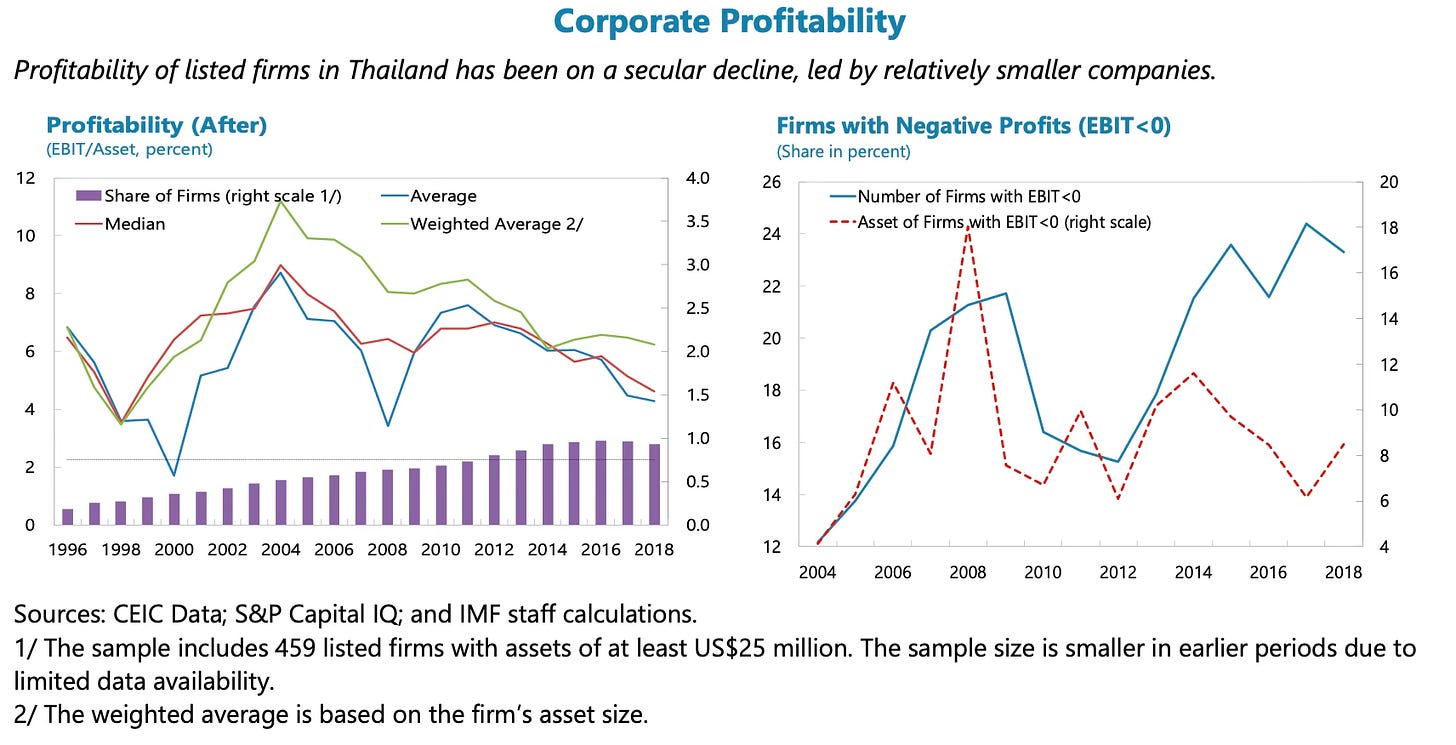

The IMF noted the same in the 2019 Article IV report and linked it to low wage growth, a direct effect of lower corporate profitability.

Firms struggled to adjust to negative revenue growth, which contributed to a weaker labour market as most likely nominal wage rigidities led to lower employment. A counterfactual world of more accommodative monetary policy would have allowed firms to lower real wages through inflation instead. This would have led to a stronger labour market and quicker household income growth.

Low profits have also impacted the ability to invest. Economic research is unclear on the direction of causation, do low profits lead to less ability to do R&D and thus low future profits or do low profits come from a lack of R&D? Tight monetary policy which impacted corporate revenue and profit growth is a reason why Thai firms have struggled to climb the global value chain.

SMEs that remain small because demand is weak are also less of a competitor to bigger corporates, resulting in a less competitive and dynamic economy.

Economic research suggests that expansionary monetary policy leads to gains for workers at smaller and younger firms, suggesting that tight monetary policy leads to losses for these same workers and firms.

Other research suggests tight monetary policy has a strong negative effect on the employment and output of the manufacturing sector.

Market competition is also reduced when monetary policy is tightened. More research suggests productivity growth increases after monetary policy is eased.

Lack of export competitiveness

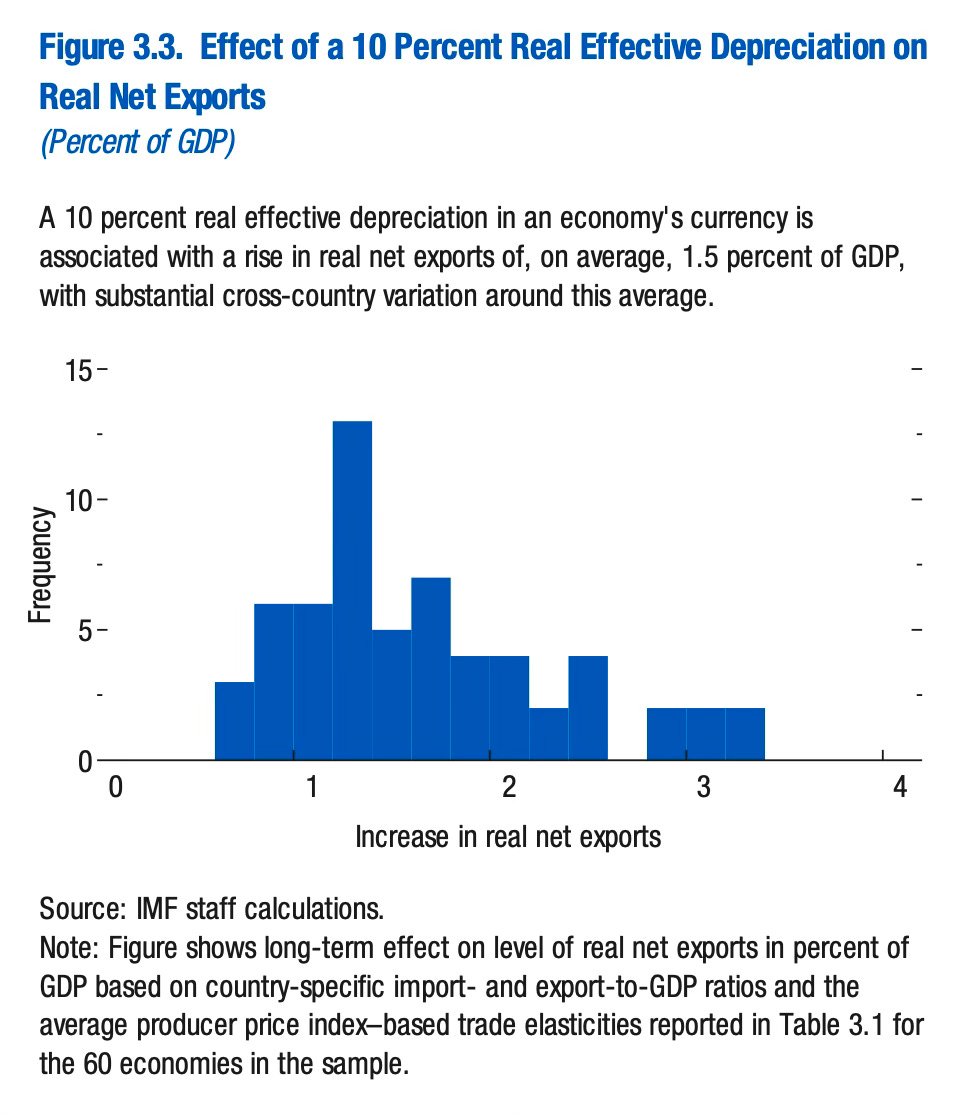

An overvalued currency led to lower export competitiveness. IMF research shows the association between a real effective depreciation and a rise in net exports.

In a counterfactual world in which monetary policy was more accommodative resulting in a weaker baht, net exports would have grown faster.

Economists have said that Thailand produces ‘old world’ products like hard-disk drives and ICE cars. But even within this group, Thailand has lost market share. Tight monetary policy that led to an overvalued currency is one reason why.

Low investment growth

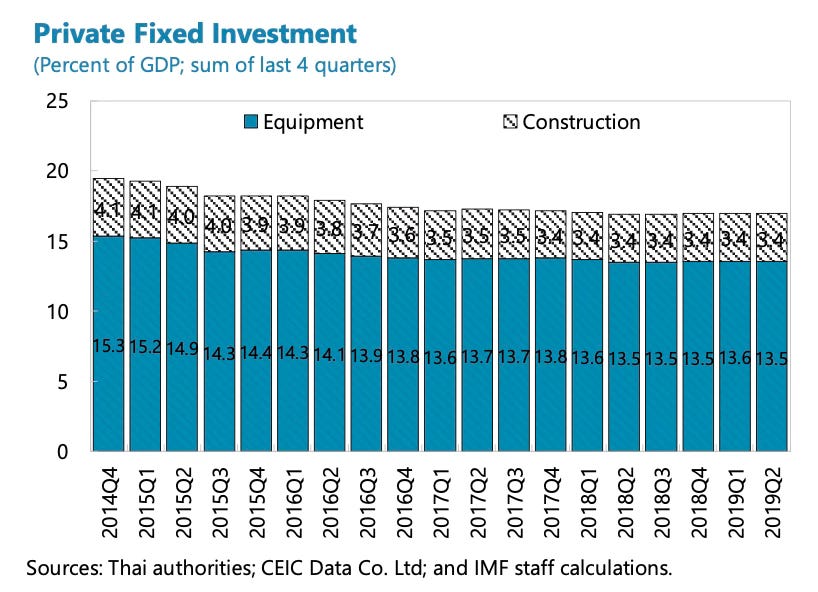

Tight monetary policy contributed to declining corporate profitability. Low corporate profitability led to low investment growth.

Private investment trended down during the period of tight monetary policy.

Slow productivity growth

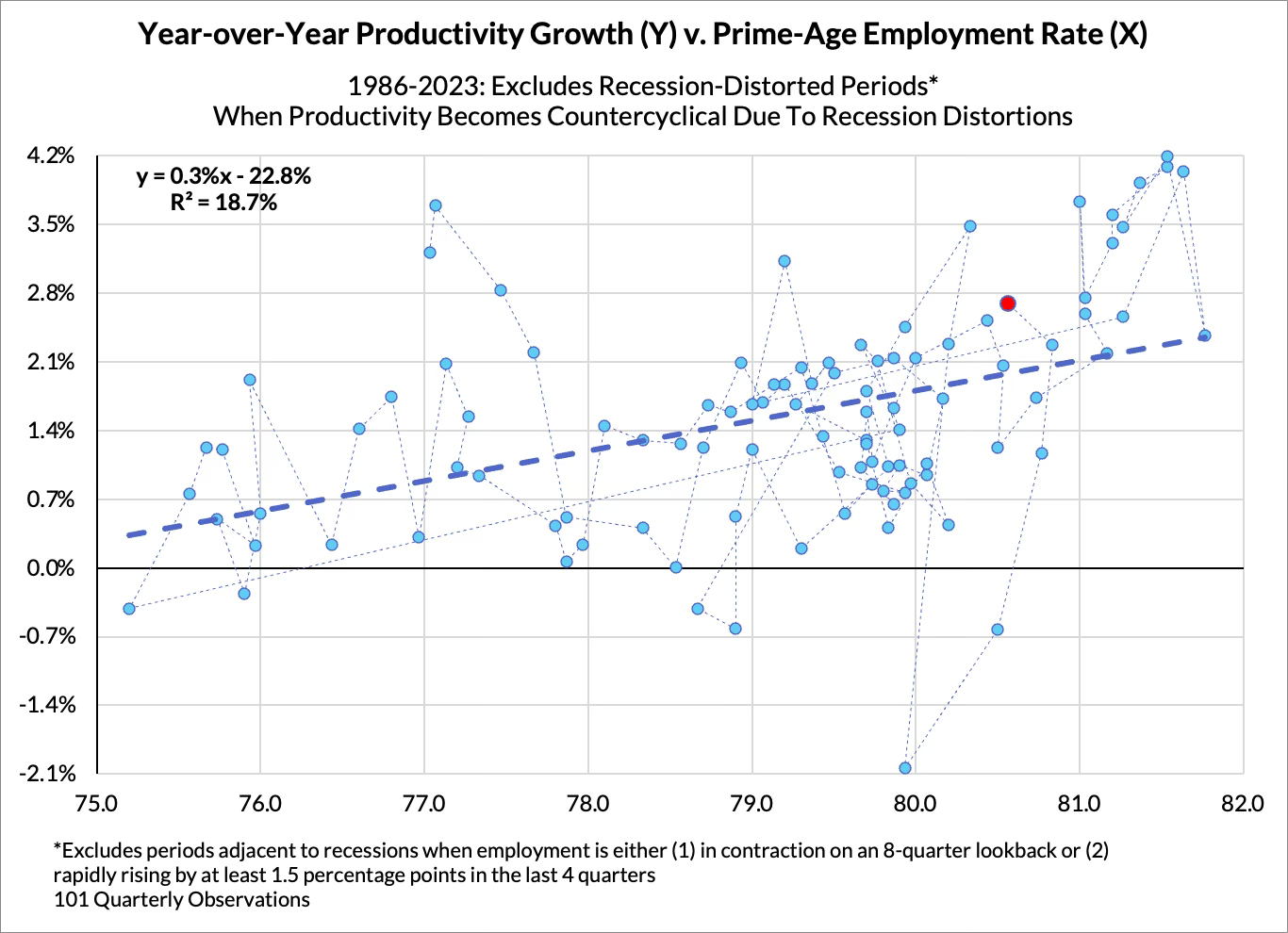

With low or negative sales and profit growth, low growth in investment and a weak labour market, productivity growth slowed. Economic research suggests tight labour markets lead to higher investment in automation. Other research suggests tight labour markets lead to higher productivity growth. Both suggest tight monetary policy contributed to less investment and lower productivity.

Tight monetary policy that contributed to a weak labour market is one reason why productivity growth has stalled. Tight monetary policy that made manufacturing exports less competitive also contributed to the productivity growth slowdown.

Jerome Powell explains the reasoning here:

Over a longer period, stronger demand should support increased investment, driving productivity higher. Moreover, as the economy tightens, firms will have rising incentives to get more out of every dollar of capital and hour of work.

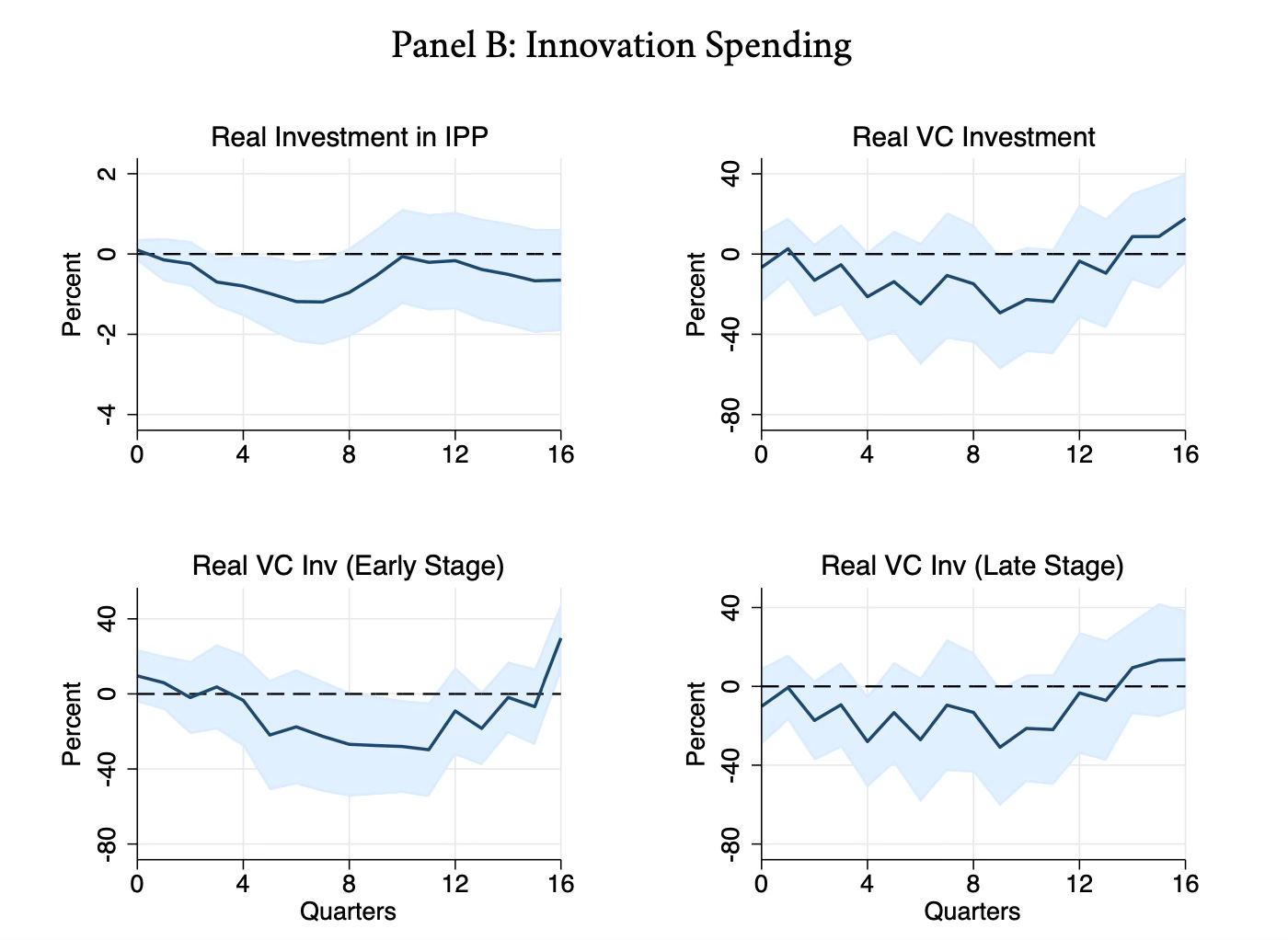

Other economic research suggests that tight monetary policy leads to a substantial negative impact on innovation activities.

Tight policy led to weak demand which led to low investment growth, a weak labour market and slow productivity growth.

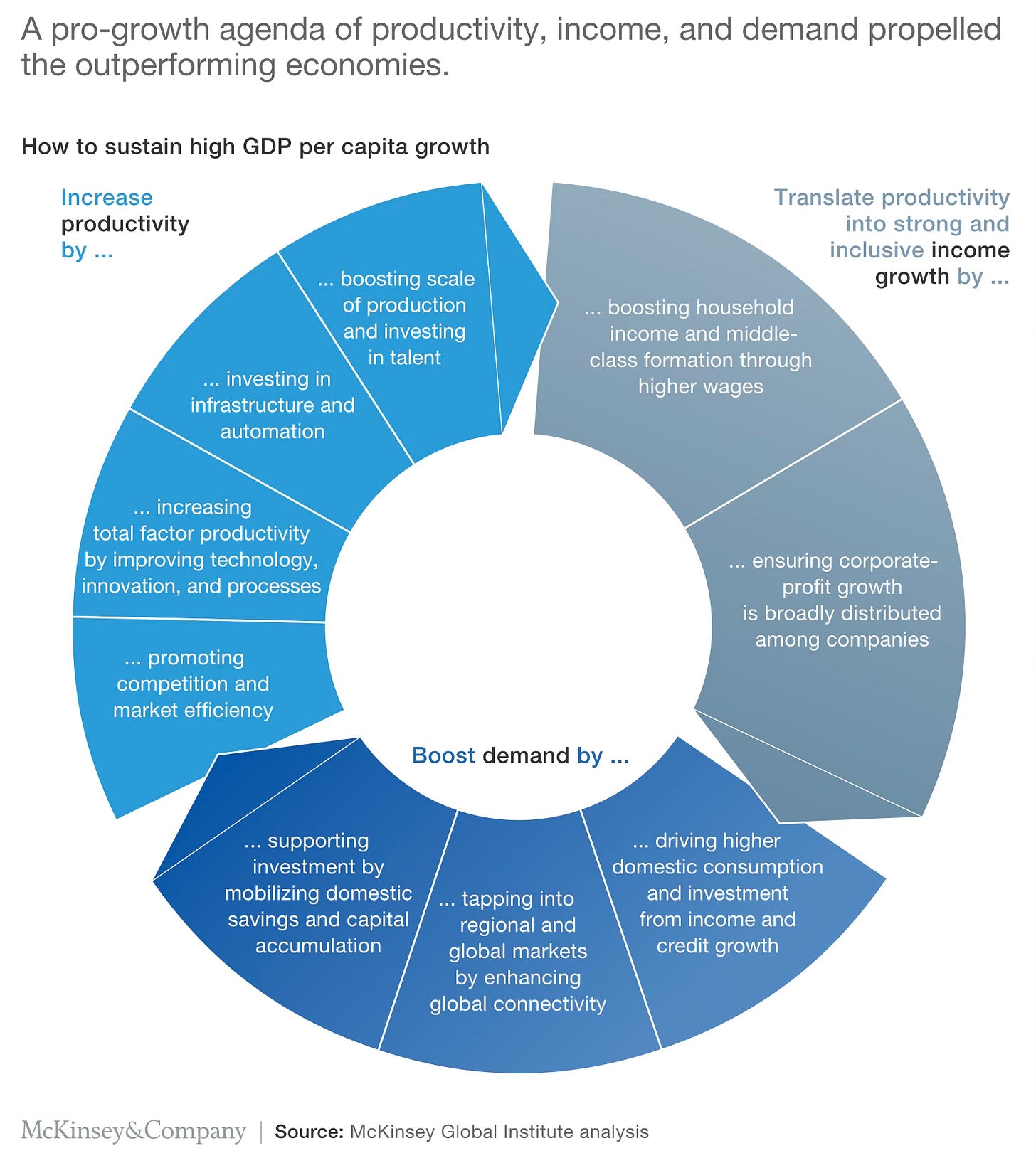

McKinsey has a neat graphic explaining the factors that lead to higher growth:

Tight monetary policy reduced demand growth, slowed down productivity growth which translated into weak and less inclusive growth.

Growth clustered in major cities

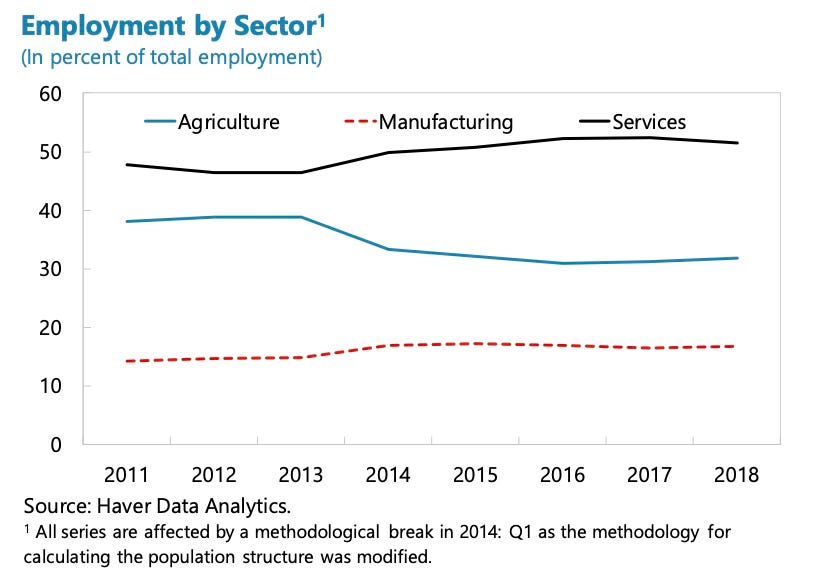

Because tight monetary policy led to an overvalued currency, manufacturing output growth slowed. Other sectors like healthcare, education and hospitality grew instead. But these sectors are clustered around major cities like Bangkok, Phuket and Chonburi. Concentrated development led to pressure on infrastructure, and contributed to a slowdown in reallocation of labour from the agricultural sector, which almost stalled during this period.

Middle to high income jobs in the service sector are also concentrated amongst higher-educated people, leading to less social mobility and less inclusive growth.

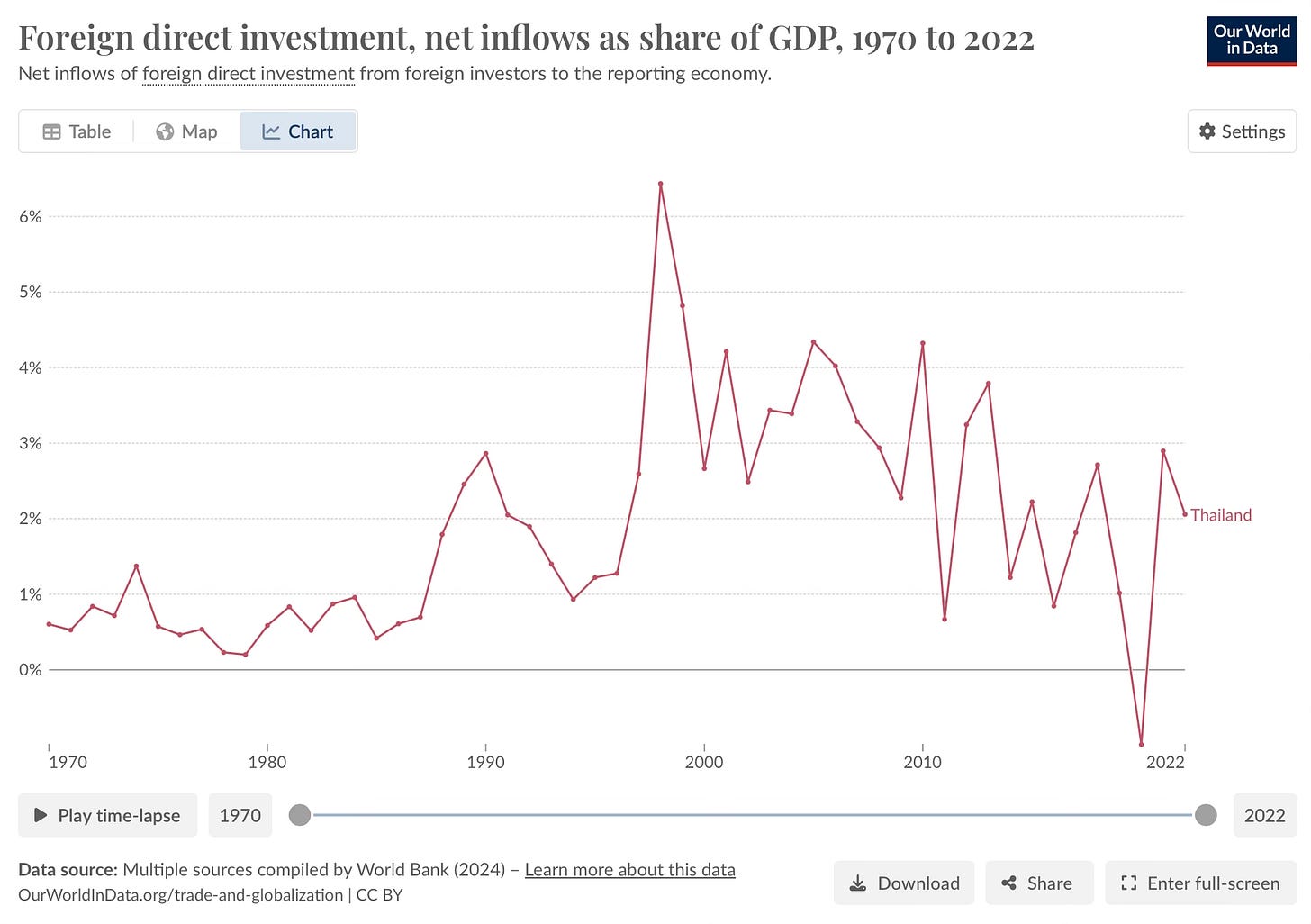

Inability to attract FDI

A slow-growing economy led to declining attractiveness as a destination for FDI. Many global firms have a ‘make where you sell’ policy, especially capital-intensive sectors like auto manufacturing.

Net FDI inflows trended down during this period of tight monetary policy.

Low FDI leads to low FDI. There are costs associated with moving factories. Firms that are moving away from China find it easy to choose Vietnam where the labour cost is lower, the currency supportive and domestic demand is growing fast instead of Thailand where the labour cost is higher, the currency a hindrance and the economy has been running below-potential for almost all of the last 10 years. A slow-growing economy is less attractive to invest in than a fast-growing economy. Slow growth leads to slow growth.

The Bank’s tight monetary policy is contributing to Thailand missing a strategic opportunity to grow its FDI.

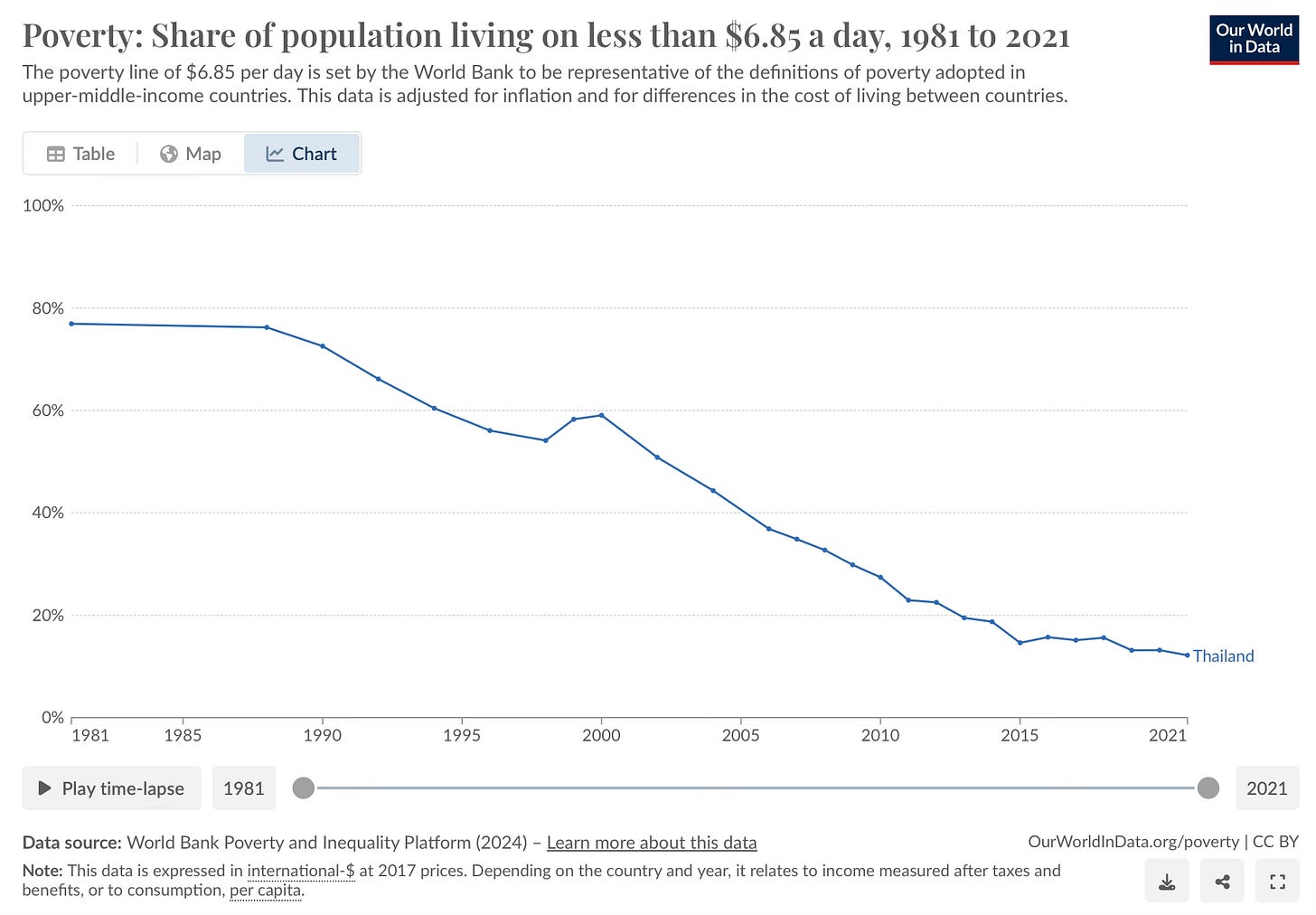

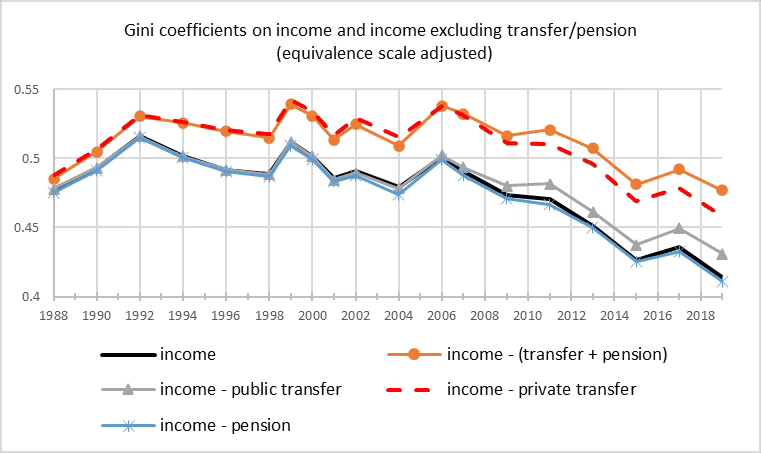

Poverty & inequality

Many measures of poverty suggest that progress in poverty reduction slowed during the last 10 years of tight monetary policy. The reduction in the share of population living on less than $6.85/day slowed. The reduction in poverty was primarily achieved through government transfers.

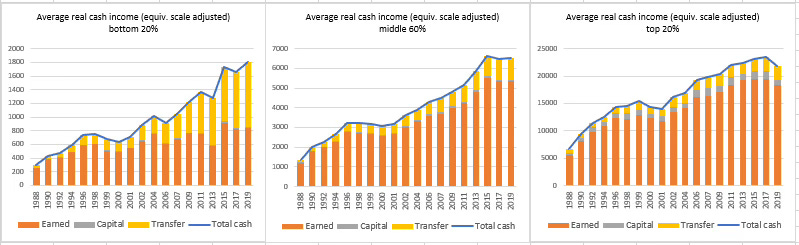

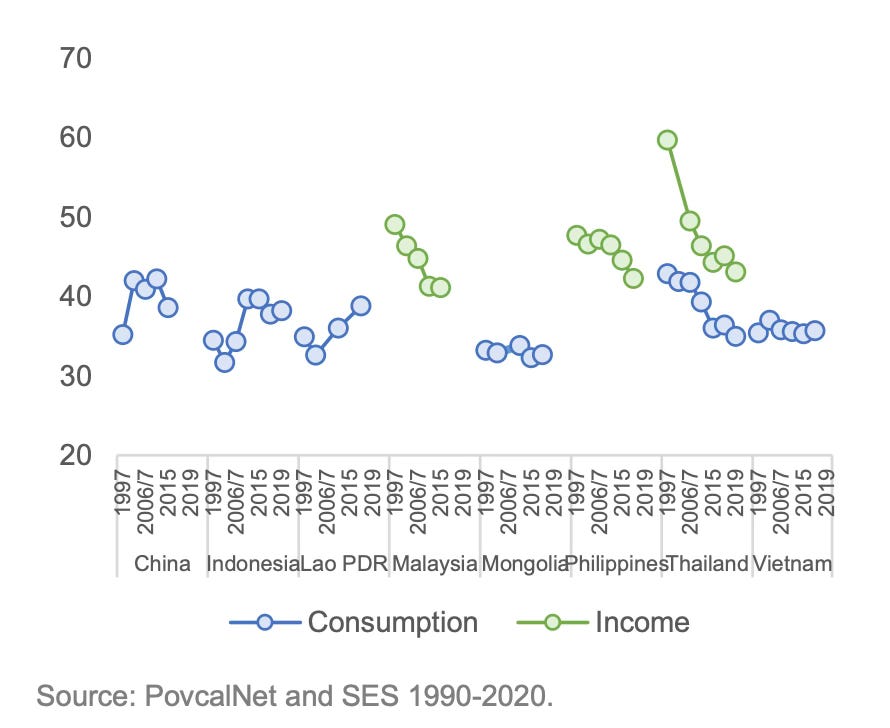

Progress on income inequality likewise slowed after 2014:

The bottom 20%’s cash income primarily grew because of transfers. Nominal earned income growth was slow.

More up to date data shows the same, with the same trend for consumption inequality:

Tight monetary policy led to many of the problems in the Thai economy today. Tight monetary policy is a cause of the structural problems the Thai economy has. Why has the Bank of Thailand erred towards tight monetary policy? What is driving the monetary policy decision-making process?

The Bank of Thailand’s framework

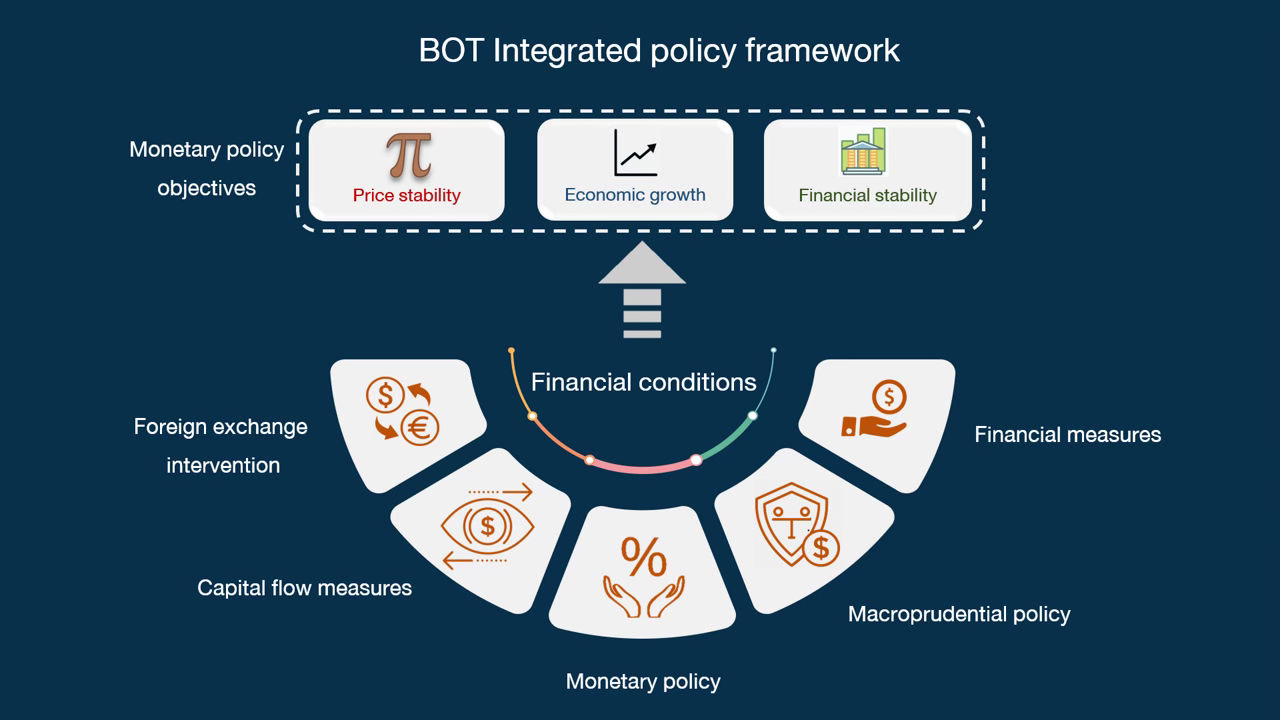

The Bank of Thailand doesn’t have a typical inflation-targeting framework. Unconventionally, its framework is described as follows:

The Bank of Thailand pursues three goals with its monetary policy: medium-term price stability, sustainable economic growth, and financial stability.

Monetary policy has an impact on both the economy and the price of goods and services. A change in the price of products and services is called an inflation rate. An inflation rate that is neither too high nor too low would promote the economic well-being in the long-term. Thus, the Bank of Thailand uses a flexible inflation targeting framework to keep the inflation rate at an appropriate level while promoting full-potential economic growth and a stable financial system.

Because all policies are interconnected, the Bank of Thailand uses a variety of policy tools to achieve its three objectives under the flexible inflation targeting framework, including monetary policy, financial policy, macroprudential policy, exchange rate policy, and capital flow policy. This is called an “integrated policy framework.” Thailand now uses a managed float exchange rate regime. Under this regime, the market mechanism determines the value of the Thai baht and the Bank of Thailand could intervene in case the currency becomes excessively volatile.

Unlike other central banks, the Bank’s framework incorporates the effects of monetary policy into financial stability concerns. Accepting that the Bank’s framework is unique, Governor Sethaput said (translated via ChatGPT):

I dare say that the Bank of Thailand is a thought leader in promoting important policy agendas that suit our context and gaining acceptance on many international platforms. We are both thought leaders and practical leaders in areas such as the Integrated Policy Framework (IPF), which emphasizes a comprehensive approach. It does not solely focus on interest rate policy but also considers the use of other tools as appropriate, including exchange rate policy, capital flow management, and macroprudential policy to manage risks to financial system stability.

Many metrics are monitored by the Bank’s economists under financial stability concerns but the most prominent one is household debt to GDP. The Bank’s economists say that household debt to GDP above 80% is a concern. The latest figure is 91%.

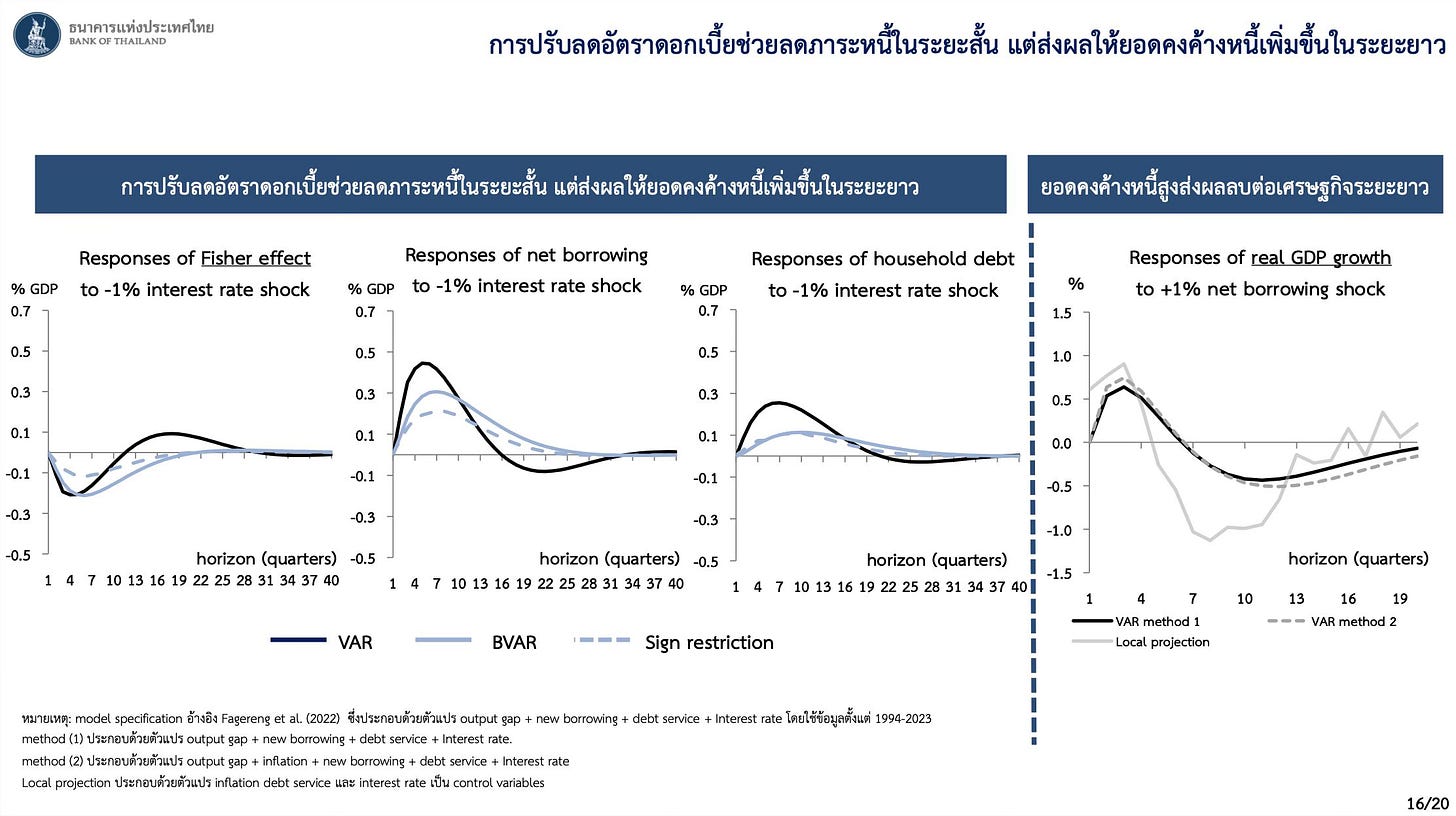

The Bank modeled the effects of what lowering interest rates by 1% would do:

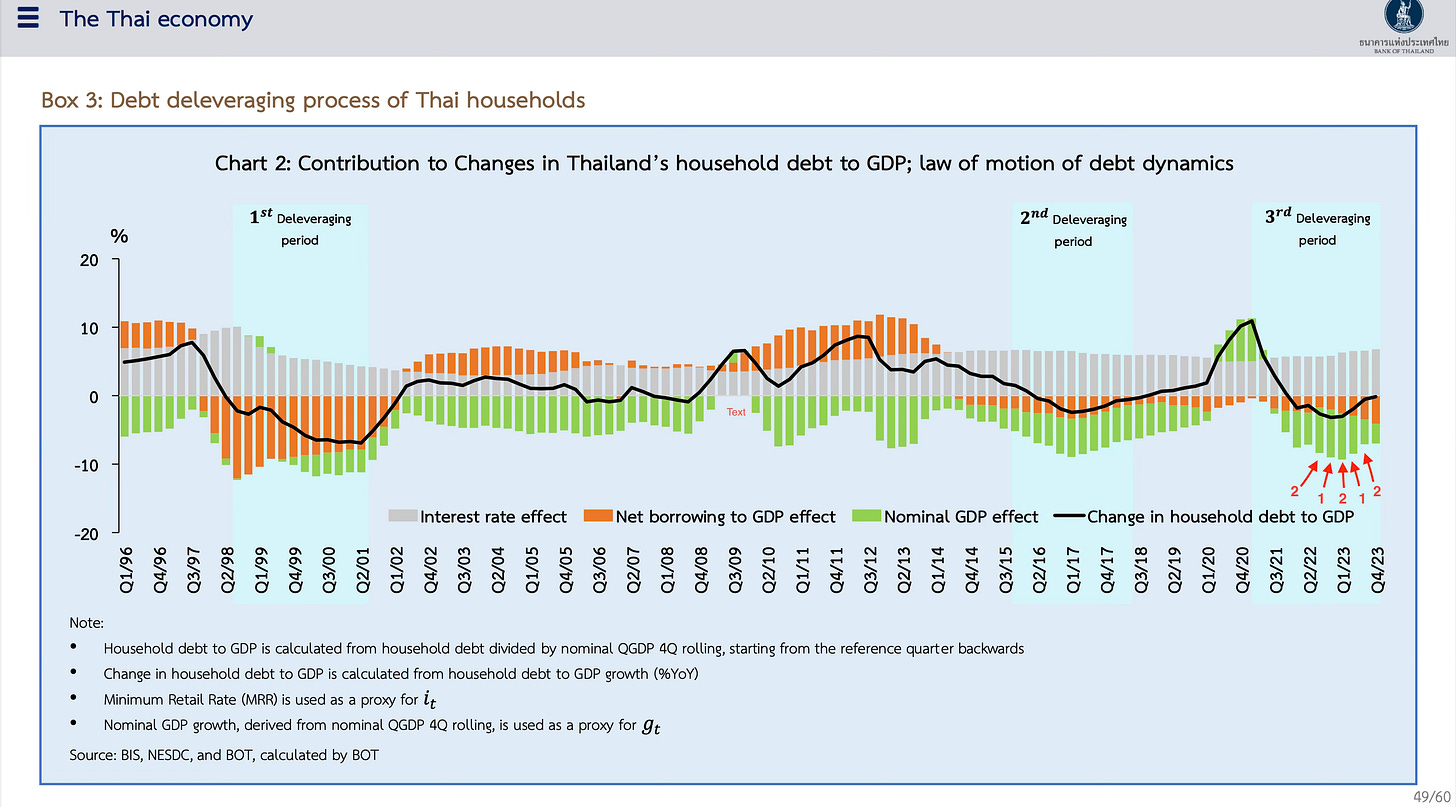

The model says that lowering rates would increase household debt to GDP. This explains why the Bank has erred towards tighter policy. This explains the Bank’s current reluctance to cut rates even while projecting that inflation would miss its target range this year. This model explains the Bank’s tolerance for below-target inflation. But this model also implies that raising rates would reduce household debt to GDP. The Bank has a graph showing the historical household debt deleveraging process:

The numbers in red that I added with arrows pointing to quarters correspond to the amount of 25bps rate rises that occurred during that quarter. In Q2-2022, the Bank raised rates twice. Instead of rate rises leading to a quicker deleveraging process like the Bank’s model implies, the further rates were raised, the slower the deleveraging process. In the last 3 quarters, household debt to GDP increased as nominal GDP growth slowed because of tight monetary policy. The labour market weakened in response to the rate rises, the unemployment rate ticked up for the first time since the reopening of the country in 2022. Total nominal earned income reported by the Labour Force Survey has declined for 5 straight months. Bank economists have not explained how the deleveraging process could continue if the labour market doesn’t improve and nominal income continues to decline.

The Bank has typically ignored household income. In its monthly and quarterly reports, the Bank typically doesn’t report changes in household income or discuss wage growth in the economy. Any discussion focuses on specific sectors instead of being economy-wide. In contrast to other central banks, the Bank does not take changes in household income into consideration for whether inflation is sustainable. Other central banks will note what increase in household income is consistent with sustainable inflation at their target. The Fed has noted that nominal incomes should rise at 3-4% per year if inflation is to settle at 2%.

40% of the Bank of England’s latest Monetary Policy Report on current economic conditions is related to the labour market and wage growth, while out of 60 pages in the Bank of Thailand’s latest Monetary Policy Report, only half a page discussed wage growth.

Evaluating the framework’s effectiveness

Given the unconventional tolerance for below-target inflation because of the weight given to the household debt problem, the expectation is that progress has been made towards its resolution. Instead, the opposite has occurred:

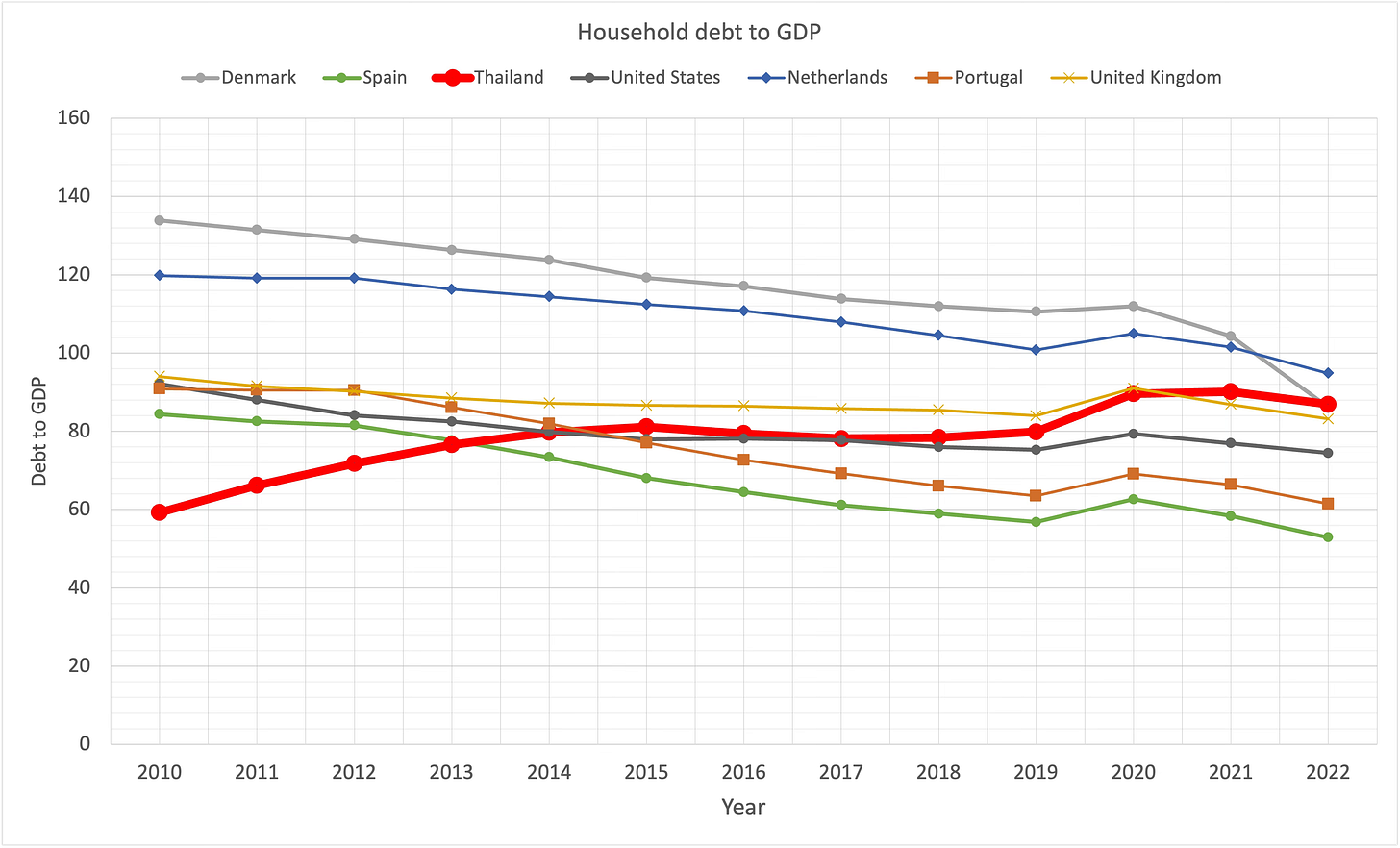

During the last 10 years in which inflation has been below target and the Bank has been reluctant to cut rates, household debt to GDP has increased. This is in contrast to other countries. Focusing on the US, the United Kingdom and Denmark, all three countries made progress in resolving their household debt to GDP issues. If we trust the Bank’s modeling regarding the link between interest rates and household debt to GDP, all three countries must have only been able to lower their ratios because interest rates were rising or were high.

However, in contrast to what the Bank’s model suggests, the US, the UK and Denmark lowered household debt to GDP ratios while interest rates were at 0 and their central banks did multiple rounds of quantitative easing.

So how did the US lower its household debt to GDP during a time when rates were at 0 and multiple rounds of QE were conducted?

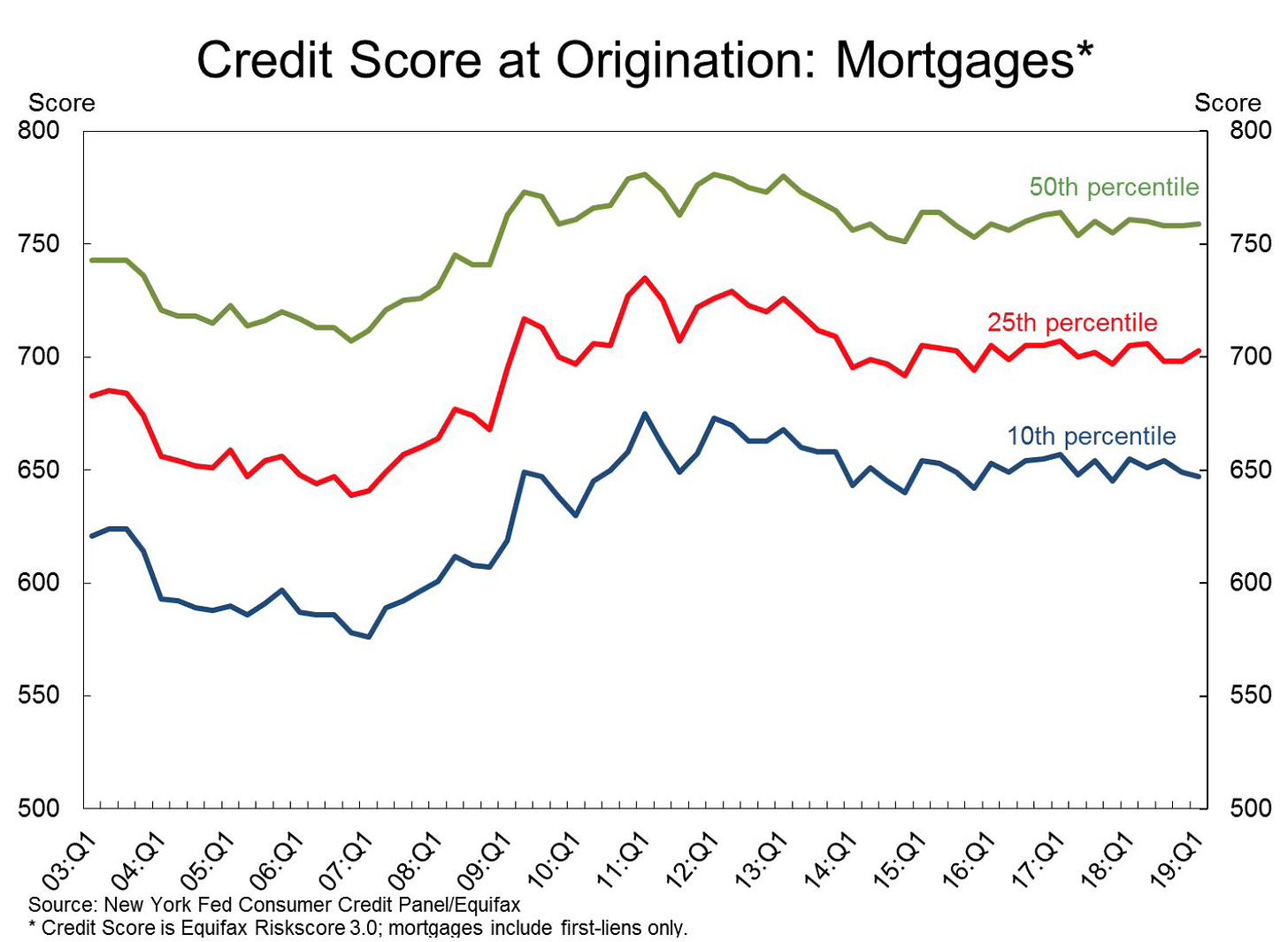

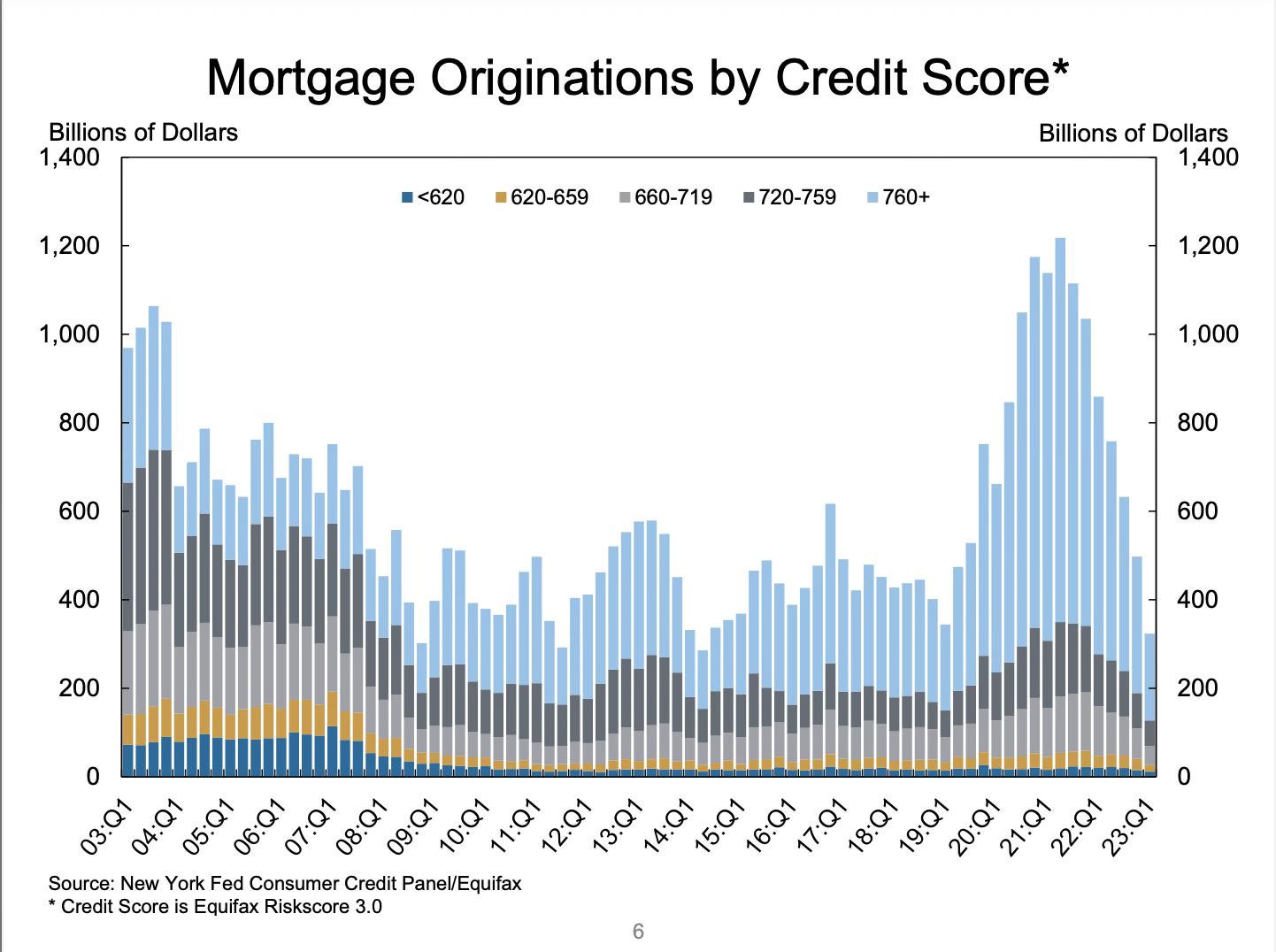

Because the Federal Reserve tightened lending standards. After the financial crisis, the average credit score for mortgages increased at all percentiles. Banks were forced to give out less loans to borrowers with low credit scores.

The data for origination by credit score suggests the same. Banks gave out less mortgages to borrowers with low credit scores.

The US’s experience suggests the best way to lower household debt to GDP is to stimulate the economy so that the labour market is tight, household income and nominal GDP grows at a steady pace while strictly controlling the borrowing by the household sector.

In contrast to what the Bank’s model suggests, household debt to GDP ratios can be lowered while rates are low. How much should we trust the Bank’s model? Bank economists have not explained why these countries had experiences that don’t fit their model. Bank economists have also not explained why Thailand can’t adopt the same strategy these countries did. Bank economists have also not explained why their model is from 2022 even though they’ve been using this framework for many years before that. Did they even have a model to support their argument that lowering rates would lead to higher household debt to GDP before 2022?

Bank economists have also repeated that the household debt deleveraging is continuing even though the debt to GDP ratio has increased for 3 straight quarters. How much should we trust the Bank’s model and its strategy?

The Bank’s framework should support its 3 goals: financial stability, price stability and sustainable economic growth.

From a financial stability standpoint, using the Bank’s preferred metric, the framework has failed; household debt to GDP has increased and is trending up.

From a price stability standpoint, the framework has also failed; inflation has been out of the target range more often than in. Inflation has missed the target 7 out of the 10 years. Looking at core inflation yields the same result.

From a sustainable economic growth perspective, IMF modeling has suggested that the economy has been running below potential for 8 out of the last 11 years (2014-2019, 2023-2024). Is below-potential growth sustainable growth? Bank economists have not made that clear. In 2013, Janet Yellen explained the Fed’s thinking:

Janet Yellen, nominated to be the next chairman of the Federal Reserve, signaled she will carry on the central bank’s unprecedented stimulus until she sees improvement in an economy that’s operating well below potential.

“A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases,” Yellen said in testimony for her nomination hearing before the Senate Banking Committee today in Washington. “Supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy.”

Yellen, the Fed’s vice chairman, voiced her commitment to using bond purchases known as quantitative easing to boost growth and lower unemployment that remains above 7 percent more than four years after the economy began to recover from the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

“Her approach is, ‘Let’s do more QE now to get the job done faster,’ ” said Laura Rosner, a U.S. economist at BNP Paribas SA in New York and a former researcher at the New York Fed. “Yellen is repeating her commitment to getting the job done.”

Yellen suggests a very accommodative policy is needed to get the economy growing at potential. Yellen and the Fed’s goal was to get the economy back to potential growth as quick as possible. This is in complete contrast to the Bank’s thinking. Who should we trust more?

Governor Sethaput has said that the Bank believes that growth will ‘converge to potential’. But how can we be confident when the Bank’s framework has delivered below-potential growth more often than not? How can the Bank be confident that growth will converge to potential when the labour market is weakening and earned income is declining? Bank economists have not explained the modeling and forecasting process. Bank economists have also not explained why the modeling and forecasting has been wrong mostly in the same direction over the last 10 years, and whether anything has changed. From this perspective, the framework has also failed.

Other tools

Given the reticence to cut interest rates, why didn’t the Bank actively use the currency to help achieve its inflation target? Why didn’t the Bank use its currency like Singapore does to lift inflation? What issue did the Bank prioritize over achieving its inflation target?

The US Treasury has a criteria for determining which countries are ‘manipulating’ its currency, which Brad Setser explains here well:

The three criteria are:

Intervention (purchases, I assume) in the foreign exchange market in excess of two percent of GDP.

A current account surplus in excess of 3 percent of GDP.

A bilateral goods surplus with the U.S. of more than $20 billion dollars.*

Thailand was very close to meeting this criteria in 2016 and came under heavy pressure from the Trump administration. Governor Veerathai was questioned about it on Bloomberg. From 2016-2018, the Bank was under constant pressure regarding foreign exchange intervention.

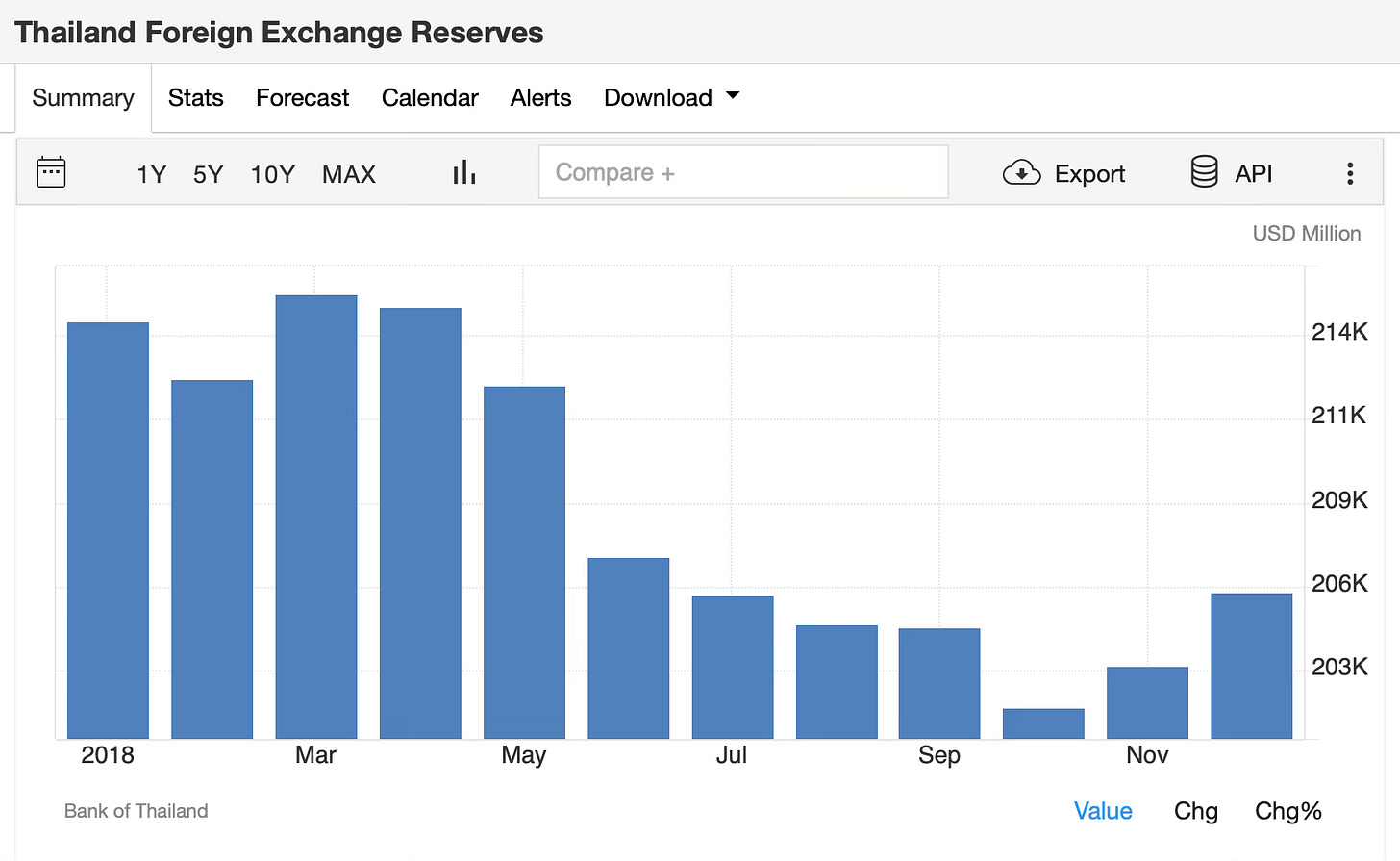

This culminated in 2018 in a year where even though headline inflation averaged only 1.1% and thus only slightly within the target range, Thailand ended up with less reported reserves than it began the year with.

It is difficult to find another example of a country that intervened in the foreign exchange market in a way that kept its currency from depreciating while inflation was far below the mid-point of its target range.

The correct action would have been to accumulate much more reserves, which would have helped depreciate the baht and lift overall inflation. GDP growth would have also been higher as a real effective depreciation would have lifted net exports.

The Bank of Thailand seemingly gave in to pressure from the US Treasury and allowed it to impact its policy-making. The Bank should have replied in the same way the Monetary Authority of Singapore usually does.

Reforming the Bank of Thailand

Changing the framework

Should the framework be changed? Because it has failed to deliver on all three of the Bank’s goals, yes it should. The Bank should adopt the same framework that other central banks have. The Fed’s framework does not mix monetary policy and financial stability:

The Fed's new framework sets a goal for inflation that averages 2 percent over time, meaning that the FOMC will now allow periods of higher inflation to make up for periods of inflation below target. On employment, the Fed's framework now emphasizes that full employment is a "broad-based and inclusive goal."

There has been no explanation given for why the Bank needs a unique framework, which is needed given that its unique framework has failed to deliver on its goals. The Bank should not experiment like it has, and the government should not allow the Bank to continue this experiment.

How should it be changed? Monetary policy should be separated like in other countries and focused only on inflation. Monetary policy should aim to not ever be tight unless inflation is sustainability above the target. The Bank should lean against tight policy. The volume of research suggests tight policy has damaging effects on the economy that lasts well over a decade. The volume of research suggests many of the structural problems the economy has today is due to tight monetary policy.

Separating monetary policy would help improve the public’s understanding of the Bank’s reaction function. Financial stability should be managed instead through rules and regulations, not interest rates. The Bank of England has two statutory authorities that manage financial stability. The Bank of Thailand should adopt the same structure.

Changing the target

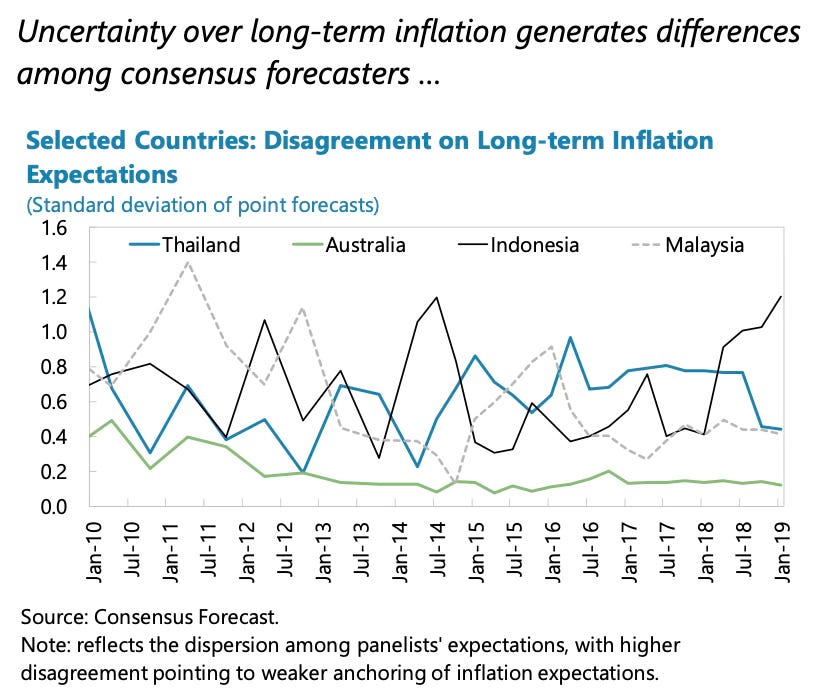

Monetary policy should also not adopt a headline inflation target. The reason for the change in 2015 was that it would enable communication to be more effective. But Thailand is an energy importer, unlike many other countries. Because it’s a small economy and only a middle-income country, energy is a bigger share of the CPI basket than in other countries. This means energy price fluctuations in global markets have a greater impact on headline inflation relative to other countries. This makes monetary policy harder to conduct, and harder to communicate. There was an increase in disagreement in long-term inflation expectations after the target was changed to a headline target.

The Bank should switch back to a core inflation target. The target functioned well in keeping inflation anchored and for the 5 years before changing the target, core inflation was in the target range for more than 95% of the time. Because Thailand is a net energy importer, core inflation better reflects demand pressures in the economy. Thailand’s gas production is also in secular decline, which means more of the CPI basket will be exposed to global price fluctuations over time, likely leading to more volatile headline inflation. If the Bank were to keep the headline target, the work required to explain its reaction function would be harder.

A core inflation target of 2-3% would be appropriate for the economy. It would require a short period of stimulus to bring up inflation but it would lead to a higher neutral rate than today, giving policy space in case of a crisis. The Bank would be less likely to encounter the zero lower bound if it adopted this target. In 2016-2018, core inflation averaged 0.7% for 3 years. The interest rate was 1.5%, suggesting a real neutral rate of 0.8%. If the Bank switched to a core inflation target of 2-3%, the policy interest rate would settle at 3-4%.

Accountability

During the last 10 years of persistent inflation misses, the Bank’s management has not demonstrated accountability. There has not been a public review of monetary policy with an explanation for why inflation has persistently undershot the target and if anything has changed within the policy-making process. This is most likely due to the Bank’s incentives. Because it was blamed for the 1997 crisis, the Bank’s incentives are to err on the conservative side. If growth is below potential, it doesn’t get blamed. Like today, the government is blamed for slow growth. The previous government was also blamed for slow growth. On the other hand, if the Bank stimulates too much, it will get blamed. The Governor admitted as much in an interview with Bloomberg:

Any push to tweak the inflation target may unanchor expectations and result in quickening price gains — and in turn, higher borrowing costs, Governor Sethaput Suthiwartnarueput said in an interview with Bloomberg Television’s Haslinda Amin in Bangkok on Tuesday.

This attitude towards accountability permeates the organisation. In interviews and briefings, Vice Governors have said that the inflation target is a medium-term target, meaning inflation misses year-to-year can be tolerated, like in 2024. This is factually incorrect. The Bank’s inflation target is both a medium-term target and a target for each year.

The Minister of Finance and the MPC mutually agreed to set the monetary policy target for price stability such that headline inflation would reside within the 1.0 – 3.0 percent target range for the medium-term horizon and for the year 2024.

The Bank’s tolerance for undershooting its target has been aptly demonstrated this year. The Bank forecasted in February that it would miss its target. It’s been 4 months since that forecast and the Bank has not made a single attempt - either through cutting rates or actively depreciating the currency - to achieve its target this year.

The Bank’s management should aim to be more accountable to the public. It is to the benefit of the organisation that it demonstrates accountability. It is difficult for the public to understand the Bank’s lack of interest in achieving its target this year, which is compounded by the management’s factually incorrect insistence that its target is only a medium-term target. The Finance Ministry can push for this by asking the Governor to testify regularly in parliament like in other countries.

Other tools

The currency should be used to help achieve the inflation target. Intentionally depreciating the baht would help increase inflation without the side-effects of cutting interest rates. Depreciating the currency would boost aggregate demand, increase household income, help lift inflation higher and lead to higher growth without leading to higher debt accumulation. Singapore and other countries have demonstrated that the currency is an appropriate tool to manage inflation.

The Bank should prioritize national interest over organisational reputation. It can ask for cover from the Finance Ministry in case the US Treasury resumes pressure. Cover can be given in the form of an agreement between the Finance Ministry and the Bank to raise foreign exchange reserves up to some months of import coverage. Current reserves are enough for 9 months of imports. An ‘agreement’ can be signed to gradually raise the level of reserves to cover 18-22 months, allowing for a continued period of reserve accumulation which would weaken the baht. The Bank could also use more typical excuses like those used in Singapore and Taiwan.

The past is the future

After implementing an inflation-target, an outsider economist reviewed it in 2000. The economist referenced Mishkin and said that undershooting the target is as costly as overshooting it. The economist also asked if the Bank could be more expansionary. That economist was Governor Veerathai.

The Bank should ask the same questions today. Can the Bank be more expansionary? What other reforms are necessary for the Bank to achieve its statutory goals?